Pavlov's reform is a government measure in the USSR aimed at reducing inflation and removing “extra” from circulation money supply.

It was carried out in early 1991, just before the fall of the Soviet Union, under the leadership of then Finance Minister Valentin Pavlov.

Where did the “extra” money come from?

By the beginning of 1991, Soviet citizens had significant sums in their hands. Some of them were represented by banknotes of 50 and 100 rubles.

In conditions of falling production and commodity shortages on the market, the value of the ruble was constantly falling. The government suspected that large banknotes from Soviet citizens were obtained through unearned income.

To overcome the current situation, it was proposed to short term carry out a measure using the surprise effect.

The program “Time” is on air...

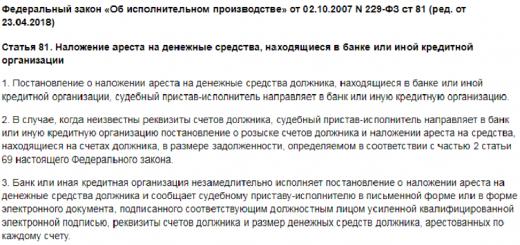

The start of the operation was announced by the “Time” program on the first channel of central television at 9 pm on January 22. The essence of the reform was as follows:

- For three days - from January 23 to 25 - Soviet citizens had to exchange old 50 and 100 ruble bills for new ones of the same denomination. After three days, old banknotes are considered invalid and can only be exchanged by decision of a special commission.

- One person had the right to exchange banknotes worth up to 1,000 rubles.

- From now on, each citizen could withdraw no more than 500 rubles per month from the USSR Savings Bank (the only bank at that time). The time for the announcement of the decree was not chosen by chance: at 21:00 savings banks, other financial institutions and the shops in the country were already closed, and the residents of the country could no longer get rid of the banknotes (exchange or buy goods with them). True, ticket offices were open in the subway and at railway stations, where the smartest citizens hurried immediately after the news was released; It was also possible to exchange with taxi drivers, who in most cases did not watch the Vremya program and did not know about the reform.

The effect of surprise was further enhanced by the fact that two weeks before the event, Pavlov categorically denied preparing any reform. Formally, it was announced that the purpose of the measure taken was to combat the flow counterfeit bills, which allegedly came from Western countries.

Pavlov's reform. exchange of 100 and 50 ruble bills photo

Pavlov's reform. exchange of 100 and 50 ruble bills photo

To emphasize the seriousness of its intentions, the government, on the eve of the launch of the reform, promoted Pavlov to his position - now he became the Prime Minister of the USSR, the first and last person in this rank. It is noteworthy that only the indicated two types of banknotes were subject to exchange. The rest of the old banknotes and coins continued to be in circulation along with the new ones.

Reform results

The Soviet government practically did not achieve its goal, except for the fact that it was possible to withdraw about 14 billion rubles from circulation. The reform did not help improve the country's economy, but rather led to the opposite effect: after its implementation, prices for most goods increased several times. And most importantly, the population’s trust in the government, already on its last legs, was completely undermined.

Currency reform became the first “shock therapy” in modern history country, which was followed by an even more “shock” - the reform activities of Yegor Gaidar. Despite their stated goals, the true essence of Pavlov’s and Gaidar’s reforms was an attempt to disguise the catastrophic state of the economy of the USSR and Russia and the corrupt “redistribution of the market.”

But in the case of Pavlov, such an effect from his reform was not conscious, but was a consequence of his character: when making any decision, the minister usually did not consult with specialists and experts, assuring that he knew everything better than others.

His name is associated primarily with the confiscation monetary reform, which, against the backdrop of the collapsing USSR, led to a complete loss of confidence in the authorities. Gazeta.Ru recalls why the Pavlovian reform happened and what it led to.

Shock therapy

On January 22, 1991, USSR President Mikhail Gorbachev signed a decree according to which old 1961 banknotes in denominations of 50 and 100 rubles were withdrawn from circulation. The announcement of the reform was made on the Vremya program at 9 pm - most banks and shops were closed. From midnight these bills stopped circulating. In three days it was necessary to have time to exchange “old” money, but no more than 1000 rubles. Restrictions also affected the ability to withdraw money from savings books - no more than 500 rubles per month.

The initiator of the reform, Valentin Pavlov, eight days before the signing of the decree, became Prime Minister of the USSR. The shock effect of confiscation on the population is also associated with the assurances of Pavlov, who many times before the decree stated that no preparations were being made for the reform.

“There are no preparations for reform. Firstly, currency reform- this is only part of a set of measures aimed at improving the economic situation, and carrying it out in isolation without solving other problems will lead to nothing. Secondly, the reform will cost the state approximately 5 billion rubles. Thirdly, the existing capacities for issuing banknotes make it possible to accumulate the required amount of new money for at least three years,” Kommersant quoted Pavlov on January 7.

On the same day, the newspaper published an article “Valentin Pavlov said that there would be no monetary reform. Oh well". A few days later, “well, well” was completely confirmed, Kommersant wrote.

The reform hit thousands of people, many of whom lost years of savings. The one-time monetary reform, carried out suddenly and without warning, became the actual confiscation of money from the population. Only a few managed to exchange “fifty dollars” and “hundreds” in advance, not trusting Pavlov’s promises, or on the same evening, before “the carriage turned into a pumpkin.” Some then managed to pay the taxi driver, while others managed to resort to other measures.

“Immediately after the message in the Vremya program, as eyewitnesses say, impatient citizens rushed to the central telegraph office to process postal orders, to the stations - to the ticket offices, where they purchased “whole” carriages in order to return the tickets later. Already on the night of January 22-23, queues began to form at savings banks. By morning they had grown tenfold,” the Izvestia newspaper wrote on January 23.

Trust is at zero

The seized banknotes were replaced by new ones from 1991. Money was changed at Sberbank, less often at the place of work and at post offices. There was excitement and panic. Many simply did not have time to exchange money - they could not get away from work, were on a business trip, were in the hospital, and so on - and lost their savings.

“We can say that the country did not work these days. In the first two days, panic reigned in society - people actually took savings banks by storm. It turned out that on the eve of the “Pavlovsk” reform, salaries were issued in 50- and 100-ruble bills, which were precisely the ones that were subject to replacement. These days turned out to be especially exciting for older people, who were afraid of not having time to hand over their old money,” writes historian Roman Kirsanov in the book “Perestroika. "New Thinking" in banking system THE USSR".

The monetary reform marked an intensification of the crisis of people's confidence in the authorities. The failed perestroika, terrible deficit and poverty gave rise to anger and a wary attitude towards any actions of the authorities.

As part of the second stage of the reform, prices for consumer goods increased two to three times from April 2. It happened as suddenly and without warning as the exchange of banknotes. This was perceived by the population as a second robbery. According to public opinion polls, it was the “Pavlovsk reform” that served as one of the main reasons for the failure of the coup attempt undertaken by the conservative part of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee and the government in August 1991, Rossiyskaya Gazeta wrote.

A fiasco on all fronts

The monetary reform was carried out under the slogan of combating counterfeit rubles imported from abroad. In addition, according to Pavlov, she had to leave the shadow sector of the economy without money and cancel funds illegally withdrawn from the country. However, the real reason was getting rid of excess cash, which was in the hands of the population and aggravated the shortage of general consumer goods.

The amount of money in circulation on January 1, 1986 should have been about 42 billion rubles, but in reality there were 71 billion rubles in circulation, Kirsanov calculated, using the normal growth rate of the State Bank money supply. By 1988, the excess money had already reached 35 billion rubles.

An attempt to stabilize the circulation of cash and partially solve the problem of shortages on the commodity market of the USSR failed. Pavlov said that the exchange of banknotes is only a small part of the planned monetary reform. The Prime Minister was preparing a comprehensive reform of pricing - the normalization of monetary circulation would be followed by a gradual liberalization of prices. But from this plan it was only possible to carry out the exchange of banknotes.

It also failed to “punish” citizens associated with the illegal economy.

Dealers in the “shadow” economy managed to place money in savings banks or successfully exchanged old banknotes for new ones.

Due to the fact that the entire population was busy exchanging money, production losses were also recorded, Kirsanov notes. It was possible to withdraw only 8-9 billion rubles, according to estimates by economist Leonid Grigoriev, who was then a member of the Commission on Economic Reform of the USSR Government. While the goal was to withdraw 81.5 billion rubles from circulation - to reduce the money supply from 133 billion to 51.5 billion. In addition, the current issue exceeded the volume of withdrawn money. National income decreased by 20% compared to 1990, the state budget deficit increased to 20–30% of GDP.

The food problem has not been resolved, but has worsened. The physical volume of retail trade turnover in January - September 1991 decreased by 12% compared to the same period in 1990, then Chairman of the State Bank Viktor Gerashchenko reported to the State Council. The consumer market was in short supply for almost all types of goods.

The Pavlovsk reform turned out to be scandalous and ineffective and caused significant damage to the population. The failure of the coup d'etat is also associated with the monetary reform. In August 1991, Pavlov was one of the organizers of the failed State Emergency Committee. On August 23, Pavlov was arrested, and on August 28, the Supreme Council of the USSR approved his resignation. In 1993, the former prime minister of the USSR was granted amnesty. For the next few years he worked in banks. In 2003 he died of a stroke.

The confiscation reform of January 1991, which in the Soviet Union is usually called “Pavlovsk” after the name of the first and last prime minister of the USSR, was considered by many to be one of the reasons for the failure of the “August putsch” of the State Emergency Committee and the collapse of the superpower. Today, when the flywheel of the second wave of the economic crisis is spinning up in the world, these events take on special implications.

At the last line

The beginning of 1991 did not promise anything good for the Soviet Union, which was bursting at the seams.

The world's largest superpower was quickly and confidently heading towards its collapse. On the national outskirts of the Empire, interethnic clashes flared up, the population of one sixth of the land was choked in gigantic queues for everything in the world, restrictions on the sale of high-quality alcohol forced traditionally drinking Soviet people to stubbornly drown out everything that even remotely resembled an alcoholic drink and uncontrollably get drunk from the surrogate. Economic reforms completely stalled, perestroika failed, glasnost finished off the exposed Stalinist remains of the CPSU.

The shortage was global. The people no longer wanted spectacles - just bread. Burglars have stopped stealing worn-out items from houses and have switched to the contents of refrigerators. Crime moved towards cooperation with the guilds and the authorities, turning into the Soviet mafia. The first cooperators grew into the first millionaires. Of the last raiders, the first were businessmen.

The army and police were decaying along with society, not understanding who to protect and for whom to fight. There were persistent rumors among the people about the transfer of the “party’s gold” abroad and its investment in profitable foreign companies. Society looked to the West with hope; the West favorably encouraged the solemn march towards the abyss of its rival Empire.

Half-starved, half-dressed, angry from the surging truth, the hopelessly ill country rolled into the 90s of the 20th century.

The transition from a planned economy to a market economy at the turn of 1980-1990 in a huge, half-starved country, accustomed from childhood to shortages and queues, was extremely painful and involved great material sacrifices for the population. Almost 300 million inhabitants, with the exception of a thin layer of party and regional elites, could not sufficiently provide themselves with food and industrial goods. Empty store shelves became a familiar sight for Soviet people in the late USSR, and modest salaries did not allow them to buy food at expensive collective farm markets and in the first commercial “lump” stores.

At the same time, it is difficult to call the citizens of the USSR at the end of socialism a “consumer society” that demanded a large amount of material goods. People lived from paycheck to paycheck, trying to provide their families first of all with decent food and secondly with a roof over their heads.

Discontent and anger grew among the broad masses, threatening to result in food riots against any government that would not be able to feed them first and provide them with essential goods. Salaries, however, were then paid carefully - their delay could definitely become a detonator for a social explosion. But the presence of constantly depreciating “wooden” rubles on hand in the absence of goods in stores made them meaningless waste paper.

According to the doctor economic sciences, Professor of the Southern Federal University Vyacheslav Volchik, “there was an excess money supply, the nature of which was the growing dysfunction of the institutions of the planned economy. Chaotic and inconsistent market reforms destroyed the central planning system, but did almost nothing to contribute to the creation of market regulatory mechanisms and institutions.”

"There are no preparations for reform"

The official reason for the financial reform was the fight against counterfeit banknotes “thrown in by enemies from abroad,” as well as the unearned income of citizens. This way it was easier to explain the idea from the point of view of the usual Soviet ideology of those years. Unofficially, everyone understood perfectly well that it was necessary to get rid of the excess money supply of banknotes printed at the end of the 1980s to fulfill the social guarantees that had accumulated in the hands of the population and were accelerating the shortage of consumer goods.

The main driver of the reform was 53-year-old Finance Minister Valentin Pavlov, who called himself a supporter of “state capitalism.” Since August 1986, he headed the USSR State Committee on Prices and was aware of not the ideological, but the real state of affairs and had long been looking for various ways confiscation from the population of unsecured goods Money.

About a dozen different concepts appeared as options, from those already tested in other countries to the most paradoxical. One of them, for example, provided for the introduction of so-called “parallel money” on the model of the gold chervonets of the 1920s, but in non-cash circulation. The other is a simple confiscation cancellation of all old money without their exchange and a mechanism for credit emission regulation (based on the experience of the Federal Republic of Germany and the harsh reform of 1948 by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who in this way actually eliminated the “black market”). The third is a compromise option in the form of a compensatory exchange with a change in scale national currency and withdrawal of savings in excess of a strictly established monetary amount.

The reform was necessary, says Vyacheslav Volchik, but the reform should not be only monetary. In the USSR at that time, deep structural reforms in the economy were long overdue. These are, first of all, reforms in the field of economic coordination and pricing. It was necessary to begin “cultivating” market institutions, which would subsequently allow the formation of markets not only for consumer goods, but also for factors of production.

Valentin Pavlov himself, having come to the post of Minister of Finance in July 1989, constantly rushed around with the idea of reform, which, according to his idea, should not only be limited to the withdrawal of excess money supply, but also lead to an increase in prices taking into account the cost of goods and services. Moreover, the minister especially insisted on carrying out the exchange as quickly as possible, so that the cash savings citizens kept not in a bank, but “in a box” either did not have time or were unable to hand over in full. The Ministry of Finance had no doubt that the overwhelming majority of the population had nothing to save from their meager salaries - only “dishonest people” were capable of keeping nest eggs in large denominations under their pillows.

In reality, problems with inflation and impoverishment of the population began in 1988 with the advent of cooperatives, says Mikhail Khazin, a well-known economist and head of an expert consulting company. - Not from each specific cooperator, but from the model itself, in which it was possible to pump money out of state enterprises through cooperatives. In order to finance social projects during the crisis, the state printed quite a lot of money in the late 1980s. They were also concentrated among a part of the population, to put it mildly, in not entirely legal ways. And Pavlov’s reform, among other things, was supposed to cut off this money.

At the same time, the minister resorted to the old “horror story”, submitting a secret note to President Mikhail Gorbachev and Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR Nikolai Ryzhkov in the summer of 1990. In it, he explained the need to exchange specifically 50- and 100-ruble banknotes of the 1961 model by the fact that allegedly these banknotes were exported in large quantities abroad, and in the USSR they were concentrated in the hands of shadow capital. The Chairman of the Council of Ministers asked customs about crossing cash across the border. From there he was informed that as a rule, scarlet ten-ruble bills flow out of the country, and not yellowish “hundred-ruble” bills.

Disputes over the radicalization of reforms first sent Ryzhkov to the hospital with a massive heart attack, and from there - the resignation of the rapidly losing popularity of Gorbachev, who needed a person who would take responsibility for future unpopular steps.

The ambitious Valentin Pavlov with his reform was perfect for this role. He was approved as prime minister on January 14, 1991. Exactly the day after the Alpha group stormed the Vilnius television center, which resulted in numerous casualties among the population of the Lithuanian capital. This investigation will later establish that provocateurs from the nationalist movement “Sąjūdis” shot at the civilian population from the rooftops. But at that time, the rise of a “state capitalist” to the leadership of the government was already firmly associated with 15 killed and 600 wounded in Vilnius. However, the future reformer Valentin Pavlov himself immediately began leading the cabinet with outright misinformation.

“There are no preparations for reform,” he assured from a high rostrum. - Firstly, monetary reform is only part of a set of measures aimed at improving the economic situation, and carrying it out in isolation without solving other problems will lead to nothing. Secondly, the reform will cost the state approximately 5 billion rubles. Thirdly, the existing capacities for issuing banknotes make it possible to accumulate the required amount of new money within three years.

Journalists from business publications pointed out to the prime minister the sealed stacks of banknotes, which they were able to photograph in various banks, and cited unnamed sources in the financial sector. But Pavlov’s “one-time lie” was echoed by the then chairman of the board of the State Bank of the USSR, Viktor Gerashchenko, who denied rumors about the upcoming reform at all angles.

Then all these lies were explained by the “increased secrecy of the operation.”

No faith, no hope, no love

Accustomed to traditional ideological hypocrisy, the country, which knew little about the market economy, vaguely suspected some kind of trick on the part of the leading and guiding party. The top officials of the state no longer inspired trust among ordinary Soviet citizens. Information about the preparation of monetary reform leaked from financial structures through acquaintances, and some managed to exchange “fifty dollars” and “hundreds” ahead of time. One of the Rostov crime bosses, who asked to be called Garik, told an RG correspondent that two days before the announcement of the reform, one of the “sponsored” cooperators showed him a home secretary filled to the brim with small banknotes exchanged by “shadow traders” through banking channels. On the eve of the “action”, part of the population managed to dump part of the “reformed” cash at the ticket offices of the metro, railway stations, taxi drivers, and shops. But there were only a few of them.

Everyone suspected the future reform, but no one knew exactly when and how it would be carried out. This was discussed in transport, in production, on collective farms, universities, expeditions, in the army, but most of those discussing it agreed that, on the one hand, “there seems to be nothing to save,” on the other, “they will still be deceived.” The truth, of course, was somewhere nearby.

On January 22, President Gorbachev signed a decree withdrawing 50- and 100-ruble banknotes of the 1961 model from circulation and exchanging them for smaller banknotes or new banknotes. At the same time, cash exchange in the amount of up to 1 thousand rubles was carried out only within three days - from Wednesday to Friday, January 23-25, and cash withdrawals from Sberbank were limited to 500 rubles. Until the end of March, it was possible to change money in special commissions, which considered each case that was not completed within the allotted time frame separately (business trip, expedition, health condition, etc.). At the same time, it was necessary to prove where the person got the amount of more than 1 thousand rubles.

The presidential decree was read out at 21.00 on the evening edition of the Vremya program, when almost all financial institutions and shops were already closed.

The smartest people panicked and rushed to save their money. Some people sent transfers in the name of their wife for all the “scorched” bills, some people bought several train or plane tickets for different flights and then handed them over. But only a few managed to do this, because there was only time until midnight.

Since Wednesday morning, gigantic queues have lined up at the savings banks, in which stood “delegates” from labor collectives, sent to change the money of entire teams. The reform organizers' bet on the "working day" partially justified itself - many were physically unable to get from the machine to the bank, to their hiding places and treasures.

However, somewhere the local authorities met the workers halfway, and money was exchanged at the post office and in production. There were fights in the queues, someone became ill, and the government then cursed at what the world was worth.

According to the same Garik, who has 17 years of “experience” of staying in remote places, in the Rostov maximum security colony its chief was offered a bribe in the amount of 500 thousand rubles so that he would release one of the local prisoners for a day under “honest thieves” "inmates" in order to change the prison "common fund". He refused. Why the boss didn’t take such an impressive jackpot is anyone’s guess. Maybe professional pride, which had not yet become an anachronism, really took hold? Or maybe he was just scared and considered it a subtle provocation. A bribe of such an amount was punishable by execution under any uniform.

The method of carrying out the reform was absolutely wrong from today’s point of view, says Vyacheslav Volchik. - But if we think like the then Soviet leadership, then there was simply no other way to carry out monetary reform. Almost all Soviet reforms were of a confiscation nature. And the 1991 reform was no exception.

As a result, about 14 billion rubles were removed from circulation, although according to the plans of the reform organizers, 51.5 out of 133 billion cash banknotes (39 percent) were subject to exchange.

At the same time, deposits in the Savings Bank were frozen. They were charged 40 percent per annum, but the money could be received in cash... only next year. And everyone remembers what happened to them after January 1, 1992.

In addition, national income decreased by 20 percent compared to 1990, and the deficit state budget in 1991 amounted, according to various estimates, from 20 to 30 percent of gross internal product.

It is interesting that after the completion of the exchange, Prime Minister Pavlov came out in the press with accusations against Western banks of coordinated activities to disrupt monetary circulation in the USSR. Moreover, as part of the second stage of the reform, also without prior announcement, from April 2 in the USSR, prices for consumer goods, which had remained stable for decades, tripled. This led to a complete loss of all trust in the government among the population, who considered themselves to have been robbed twice. According to public opinion polls, it was the “Pavlovsk reform” that served as one of the main reasons for the failure of the coup attempt undertaken by the conservative part of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee and the government in August 1991. It is noteworthy that the failed reformer Valentin Pavlov also appeared in the State Emergency Committee at that time...

It may seem ambiguous,” he later recalled, “but the fact is that very few people at that time understood and believed that the issue was not about ideology. The question is not about forms of ownership, about management, about reforms, but about the state.

But that was all later. And then, at the end of January 1991, the country's residents said goodbye not only to the missing “stash,” but also to part of their common past. Residents of Vladikavkaz (just renamed from the Soviet Ordzhonikidze) still remember how on the morning of January 26, 1991, a day after the exchange of banknotes stopped, a well-dressed man with a suitcase approached the State Bank building. He opened it, dumped a mountain of fifty rubles into the snow and set it on fire for the amusement of passers-by. Together with them, faith in “the mind, honor and conscience of our era” burned in the flames of the most expensive fire in North Ossetia.

On January 22, 1991, the last Soviet monetary reform began, called “Pavlovskaya” in honor of its creator, Minister of Finance and later Prime Minister of the USSR Government Valentin Pavlov. This was a confiscatory monetary reform, which pursued the goal of getting rid of the “extra” money supply in cash circulation and at least partially solving the problem of shortages on the commodity market of the USSR. The formal reason for the reform was the fight against counterfeit rubles allegedly imported into the USSR from abroad.

On January 22, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev signed the Decree “On stopping the acceptance for payment of USSR State Bank banknotes in denominations of 50 and 100 rubles, model 1961, and limiting the issuance of cash from citizens’ deposits.” The signing of the Decree was announced in the Vremya program, when almost all financial institutions and shops were already closed.

After the completion of the exchange of large sums of money, Pavlov appeared in the press accusing Western banks of coordinated activities to disrupt monetary circulation in the USSR.

As a result of the reforms, the government's plans were only partially realized: the confiscation procedure made it possible to withdraw 14 billion cash rubles from circulation (approximately 10.5% of the total, or slightly less than 17.1% of the 81.5 billion planned for withdrawal).

On April 2, 1991, prices for food products, transport, and utilities were increased 2-4 times.

In December 1991, experts from the Kommersant newspaper summed up the results of the entire year 1991 and found that, taking into account the “Pavlovsk” reform, prices increased 7.8 times over the year. Wherein greatest contribution It was not market factors that contributed to the price race, but various kinds of force majeure circumstances, such as the exchange of banknotes and official statements about upcoming cataclysms in monetary circulation.

There was a decline in the living standards of the population. By the end of 1991, the USSR economy found itself in a catastrophic situation. The decline in production accelerated. National income decreased by 20% compared to 1990. The state budget deficit, i.e. the excess of government expenditures over revenues, amounted, according to various estimates, from 20% to 30% of gross domestic product (GDP). The increase in the money supply in the country threatened the loss of state control over financial system and hyperinflation, that is, inflation of over 50% per month, which could paralyze the entire economy.

The main consequence of the reform was the loss of public confidence in the actions of the government. Many politicians and historians believe that the political and financial reforms carried out in the USSR in 1991 completely undermined the trust of USSR citizens in the union leadership and had a significant impact on subsequent events (the August putsch, the Belovezhskaya Agreement).

The material was prepared based on information from open sources

Many people remember in which year Pavlov’s reform led to the final impoverishment of the Soviet people. It is customary to call her by the name of the first and, in fact, the last prime minister of the Soviet Union. Let us further consider what the Pavlovian reform of 1991 was: the reasons, stages, consequences of the reforms.

The situation in the country

The beginning of 1991 did not bode well for the collapsed one. On the outskirts of the country, interethnic clashes became more frequent, there was a global shortage in stores, and people lined up in huge queues. Gorbachev's economic reforms did not lead to anything, perestroika did not take place. The government tried to switch from planned to market system management. However, institutionally the state turned out to be unprepared for this - the country lacked the necessary people and bodies. The overwhelming majority of the population could not provide themselves with sufficient food and industrial goods. People are used to empty shelves. The only positive development at that time was the stable payment of a modest salary. Of course, the country's leadership understood that if they began to delay wages, this would result in mass protests. And the government could not allow this to happen. People, meanwhile, did not demand a large amount of material wealth. The population of the USSR was accustomed to restrictions, shortages, and isolation. Everyone lived from paycheck to paycheck, trying to provide their families first with food and second with housing. According to prof. Volchik, the nature of the existing excess money supply was determined by the growing dysfunctions of the institutions of the planned economic regime. Inconsistent and chaotic transformations destroyed the centralized system, but did not contribute to the formation of market regulatory mechanisms and institutions.

Why did the Pavlovsk reform of 1991 begin?

There was a lot of money in the country. However, in the current crisis conditions, they constantly depreciated in value and turned into meaningless waste paper. The official reason given was the fight against counterfeit banknotes “thrown in from abroad.” In addition, the government decided to confiscate citizens' unearned income. This statement of reasons was the most common for Soviet ideology. Unofficially, it was clear to everyone that the key goal was the elimination of banknotes printed in the late 80s. to fulfill social guarantees that had accumulated among the population and increased the shortage of consumer products.

Organizer of change

The author of the reform was Valentin Pavlov, a 53-year-old "supporter of the Minister of Finance. Since 1986, he headed the USSR State Committee on Prices. Accordingly, he knew not the ideological, but the real state of affairs. Pavlov had long been looking for different ways to withdraw funds from the population, unsecured Since taking up his ministerial post in July 1989, he has been constantly mulling over the idea of reform.According to his plan, the reform included not only the withdrawal of excess money, but also the promotion of higher prices, taking into account the cost of services and goods.

Transformation options

Pavlovskaya city suggested several concepts. Among them were those that had previously been used in other countries. Quite paradoxical concepts have also been developed. For example, one of the options was the introduction of “parallel money” following the example of the 20s, but in non-cash circulation. Another concept involved simply confiscatory cancellation of previous banknotes without exchange and a mechanism for issuing credit regulation. Such transformations were carried out in 1948 in Germany by Chancellor Adenauer. As a result, it was actually eliminated. There was another, compromise option that could have been followed by the Pavlovian reform of 1991. People didn’t have much money, compensation for which was supposed to be within a strictly established amount. However, the management intended to carry out an exchange with a change in the scale of the national currency. This provided for the withdrawal of savings in excess of a strictly defined amount. The minister insisted on carrying out reforms as quickly as possible, so that people either would not have time or would not be able to hand over the funds stored not in banks, but “in little money boxes”. The Ministry of Finance had no doubt that the majority of the population had nothing to save from their meager salaries, and only “dishonest people” could keep nest eggs in large denominations.

Rationale for transformations

The Pavlovsk reform of 1991 had to be approved by Gorbachev. To do this, it had to be justified. Pavlov used a long-known method. In the summer of 1990, he submitted a secret note addressed to Gorbachev and Ryzhkov. In it, the minister explains the need to exchange exclusively 50 and 100 ruble bills of 1961. because they are exported abroad in huge quantities. Ryzhkov, being the chairman of the Council of Ministers at that time, requested confirmation from the customs authorities. From there they reported that, as a rule, ten-ruble notes cross the border, not hundred-ruble notes. A discussion began, as a result of which Ryzhkov was dismissed. Gorbachev, who was rapidly losing popularity among the masses, needed a person who would take responsibility for the upcoming steps. Pavlov was excellent for this role. On January 14, 1991, his candidacy was approved for the post of prime minister.

Leadership of the Cabinet of Ministers

Pavlov began his activities as Prime Minister with disinformation. From a high rostrum, he assured that no preparations were being made for future reforms. He said that financial reforms are only part of a whole range of measures aimed at improving the economy. Carrying out monetary reform in isolation without solving other problems is pointless, since it will not lead to any results. In addition, the prime minister said that the transformation would cost the economy 5 billion rubles. And at the end of his speech, he pointed out that the banknote production capacity that existed at that time would make it possible to accumulate the required volume of new banknotes within three years.

Unrest among the people

Soviet citizens, who have long been accustomed to the ideological attacks of the leadership, poorly understand the essence market economy, still felt some kind of trick on the part of the party. The top officials of the state have already ceased to enjoy any kind of trust. Information about the upcoming reform leaked through friends, so some citizens managed to change their “hundreds” and “fifty kopecks” in advance. On the eve of the announcement of the exchange, part of the population managed to “exchange” cash at the ticket offices of stations and subways, in shops, and with taxi drivers. However, there were only a few such “lucky” ones. Everyone suspected the reform, but no one knew when or how it would be carried out. The upcoming changes were discussed everywhere: in transport, in universities, on collective farms, in production, in the army. The majority of the population came, on the one hand, to the conclusion that “there is, in fact, nothing to save,” and on the other, “they will be deceived anyway.”

Pavlovsk money reform: the course of the “action”

On January 22, Gorbachev signs a decree according to which 50 and 100 ruble banknotes dating from 1961 are withdrawn from circulation. and exchanged for smaller new bills. From that moment on, the Pavlovsk reform of 1991 began. The population had less money than expected. Cash exchange in the amount of up to 1 thousand rubles. was carried out only for three days - from January 23 to 25 (Wednesday to Friday). At the same time, withdrawal of money from accounts in Sberbank was limited to 500 rubles. The exchange was allowed until the end of March, but in special commissions. They considered each case of missing the deadline separately. At the same time, the citizen had to tell where he got the amount of more than 1 thousand. The presidential decree was read out at 9 pm, when almost all organizations were no longer working. The smartest citizens began to panic and save their money. Someone urgently sent a transfer, someone bought several plane or train tickets for different flights in order to return them later. However, only a few managed to do all this.

Exchange process

The Pavlovsk reform created huge queues already on the morning of January 23. At the Sberbank cash desks there were “delegates” of labor collectives who changed the banknotes of entire teams. Management's calculations for working days were partially justified. Many citizens simply did not have time to get from production to cash registers. However, in some areas the local administration met the population halfway. Exchange offices were opened in production and in post offices. Conflicts arose in the queues themselves, and some people became ill. As a result, the Pavlovsk monetary reform made it possible to withdraw about 14 billion rubles from the population. According to the organizers’ plan, of course, it was supposed to confiscate more than 51.5 billion out of 133 billion (about 39%). The Pavlovsk reform, in addition, included a freeze on bank savings. These funds were accrued at 40% per annum. However, they could not be received until next year.

results

The Pavlovian reform sharply reduced national income. Compared to 1990, it decreased by 20%. At the same time, the budget deficit increased significantly. According to various estimates, in 1991 it amounted to 20-30% of GDP. When the Pavlovian reform was completed, its organizer made accusations against foreign banks, reproaching them for coordinated activities aimed at disrupting the circulation of cash in the USSR. As part of the second stage of reforms, without any prior announcement, prices for consumer products in the country jumped sharply from April 2, despite the fact that they had remained at a stable level for decades. All this led to an absolute loss of all confidence in the party leadership. The population considered themselves to have been robbed twice.

Conclusion

As the results of public opinion show, the Pavlovian reform became one of the key reasons for the failure of the coup. As is known, it was undertaken by conservatives from the government and the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee in 1991. It is noteworthy that reformer Valentin Pavlov was also present among the members of the Emergency Committee. Subsequently, he said that at that time few people realized and believed that it was not an ideological issue that was being resolved. At the end of January 1991, the country's population said goodbye not only to the missing banknotes, but also to part of their past. People living in Vladikavkaz, who witnessed these events, even now often recall how on January 26, a day after the general excitement, a well-dressed man with a suitcase appeared at the State Bank building. He opened it and poured a pile of 50-ruble banknotes into the snow and set them on fire. From the point of view of modern times, according to Volchik, this form of reform is absolutely unacceptable. However, if we assess the situation the way the previous leadership did, then there was simply no other way of financial transformation. Almost all reforms of the USSR were of a confiscatory nature. And this “action” of the early 90s was no exception.