The basis of the Russian economy in the second half of the 17th century was serfdom. However, along with it, new phenomena are found in the economic life of the country. The most important of these was the folding of all Russian market. In Russia of this time, small-scale commodity production and money circulation develop, and manufactories appear. The economic disunity of individual regions of Russia is beginning to recede into the past. The formation of an all-Russian market was one of the prerequisites for the development of the Russian people into a nation ( See V. I. Lenin, What are “friends of the people” and how do they fight against the Social Democrats? Works, vol. 1, pp. 137-138.).

In the 17th century there was a further process of formation of the feudal-absolutist (autocratic) monarchy. Zemsky Sobors, which met repeatedly in the first half of the century, finally ceased their activity by the end of the century. The significance of the Moscow orders has increased as headquarters with their bureaucracy represented by clerks and clerks. In his domestic politics autocracy relied on the nobility, which becomes a closed estate. There is a further strengthening of the rights of the nobility to land, and landownership is spreading in new areas. The "Cathedral Code" of 1649 legally formalized serfdom.

The strengthening of feudal oppression met with fierce resistance from the peasants and the lower classes of the urban population, which was expressed primarily in powerful peasant and urban uprisings (1648, 1650, 1662, 1670-1671). The class struggle was also reflected in the largest religious movement in Russia in the 17th century. - schism of the Russian Orthodox Church.

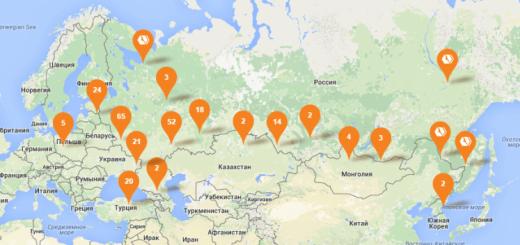

The rapid economic growth of Russia in the 17th century contributed to the further development of the vast expanses of Eastern Europe and Siberia. In the 17th century there is an advance of Russian people to the sparsely populated territories of the Lower Don, the North Caucasus, the Middle and Lower Volga regions and Siberia.

The reunification of Ukraine with Russia in 1654 was an event of great historical significance. The kindred Russian and Ukrainian peoples united in a single state, which contributed to the development of productive forces and the cultural upsurge of both peoples, as well as the political strengthening of Russia.

Russia, 17th century acts in international relations as a great power, stretching from the Dnieper in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east.

Serfdom

In the second half of the XVII century. The main occupation of the population of Russia remained agriculture, based on the exploitation of the feudally dependent peasantry. In agriculture, the methods of tillage that had been established in previous times continued to be used. Three fields were most common, but in the forest regions of the North, undercutting occupied an important place, and in the steppe zone of the South and the Middle Volga region - fallow. Primitive tools of production (plow and harrow) and low yields corresponded to these methods of cultivating the land, characteristic of feudalism.

The land was owned by secular and spiritual feudal lords, the palace department and the state. Boyars and nobles by 1678 concentrated in their hands 67% of peasant households. This was achieved through grants from the government and direct seizures of palace and black-moss (state) lands, as well as the possessions of small service people. The nobles created serf farms in the uninhabited southern districts of the state. By that time, only a tenth of the taxable (that is, those who paid taxes) population of Russia (townspeople and black-skinned peasants) was in an unenslaved state by this time.

The overwhelming majority of secular feudal lords belonged to the middle and small landowners. What was the economy of a middle-class nobleman can be seen from the correspondence of A.I. Bezobrazov. He did not disdain any means if the opportunity presented itself to round off his possessions. Like many other landowners, he vigorously seized and bought up fertile lands, shamelessly driving out small servants from their homes, and resettled his peasants from the less fertile central districts to the South.

The second place after the nobles in terms of land ownership was occupied by spiritual feudal lords. In the second half of the XVII century. Bishops, monasteries and churches owned over 13% of taxable households. The Trinity-Sergius Monastery stood out especially. In his possessions, scattered throughout the European territory of Russia, there were about 17 thousand households. The votchinniki-monasteries ran their households in the same serf ways as the secular feudal lords.

In a few best conditions in comparison with the landlord and monastic peasants, there were black-haired peasants who lived in Pomorie, where there was almost no landownership and land was considered state owned. But they were also burdened with various kinds of duties in favor of the treasury, they suffered from the oppression and abuses of the royal governors.

The center of the estate or patrimony was a village, or village, next to which stood the master's estate with a house and outbuildings. A typical manor yard in central Russia consisted of a chamber set on the basement floor. With her were the canopy - a spacious reception room. Outbuildings stood next to the upper room - a cellar, a barn, a bathhouse. The yard was fenced, next to the garden. The estates of the wealthy nobles were more extensive and luxurious than those of the small landowners.

The village, or village, was the center for the villages adjacent to it. In a medium-sized village, there were rarely more than 15-30 households, in the villages there were usually 2-3 households. Peasant yards consisted of a warm hut, cold vestibules and outbuildings.

The landowner kept serfs in the estate. They worked in the garden, barnyard, stables. The master's household was in charge of the clerk, the confidant of the landowner. However, the economy, which was carried out with the help of courtyard people, only partially satisfied the landowners' needs. The main income of the landowners was brought by corvée or quitrent duties of serfs. The peasants cultivated the landlords' land, harvested crops, mowed meadows, carried firewood from the forest, cleaned ponds, built and repaired mansions. In addition to the corvee, they were obliged to deliver to the masters "table stocks" - a certain amount of meat, eggs, dry berries, mushrooms, etc. In some villages of the boyar B. I. Morozov, for example, it was supposed to give a pig carcass, two ram, goose with giblets, 4 piglets, 4 hens, 40 eggs, some butter and cheese.

The increase in domestic demand for agricultural products, as well as, in part, the export of some of them abroad, prompted the landowners to expand the lordly plowing and increase the dues. In this regard, peasant corvee was continuously increasing in the black earth belt, and in the non-chernozem regions, mainly central (with the exception of estates near Moscow, from which supplies were delivered to the capital), where corvée was less common, the share of quitrent duties increased. The landowner's plowing expanded at the expense of the best peasant lands, which went under the master's fields. In areas where quitrent prevailed, the value of monetary rent slowly but steadily increased. This phenomenon reflected the development of commodity-money relations in the country, in which peasant farms were gradually involved. However, in its pure form, cash dues were very rare; as a rule, it was combined with the rent of products or with corvee duties.

A new phenomenon, closely connected with the development of commodity-money relations in Russia, was the creation of various types of fishing enterprises in large landlord farms. The largest estate of the middle of the XVII century. boyar Morozov organized the production of potash in the Middle Volga region, built an ironworks in the village of Pavlovsky near Moscow, and had many distilleries. This hoarder, according to contemporaries, had such a greed for gold, "like an ordinary thirst for drink."

Morozov's example was followed by some other major boyars - Miloslavsky, Odoevsky and others. At their industrial enterprises, the most burdensome work of transporting firewood or ore was assigned to the peasants, who were obliged in turn to work sometimes on their own horses, leaving their arable land abandoned in the hottest time of field work. . Thus, the passion of large feudal lords for industrial production did not change the feudal foundations of the organization of their economy.

Large feudal lords introduced some innovations in their estates, where new varieties of fruit trees, fruits, vegetables, etc. appeared, and greenhouses were built for growing southern plants.

The emergence of manufactories and the development of small commodity production

An important phenomenon in the Russian economy was the foundation of manufactories. In addition to metallurgical enterprises, leather, glass, stationery and other manufactories arose. The Dutch merchant A. Vinius, who became a Russian citizen, built the first water-powered ironworks in Russia. In 1632, he received a royal charter for the construction of factories near Tula for the production of iron and iron, casting cannons, boilers, etc. Vinius could not cope with the construction of factories on his own and a few years later entered into a company with two other Dutch merchants. Large iron-working plants were created somewhat later in Kashira, in the Olonets region, near Voronezh and near Moscow. These factories produced cannons and gun barrels, strip iron, boilers, frying pans, etc. In the 17th century. the first copper-smelting plants appeared in Russia. Copper ore was found near Salt Kamskaya, where the treasury built the Pyskorsky plant. Subsequently, on the basis of the Pyskorsky ores, the factory of "smelters" of the Tumashev brothers operated.

Work in the manufactories was carried out mainly by hand; however, some processes were mechanized with water engines. Therefore, manufactories were usually built on rivers blocked by dams. Labor-intensive and cheaply paid work (earthworks, logging and transportation of firewood, etc.) was carried out mainly by ascribed peasants or their own serfs, as was the case, for example, at the ironworks of the royal father-in-law I. D. Miloslavsky. Shortly after their foundation, the government attributed two palace volosts to the Tula and Kashira factories.

The decisive role in providing the population with industrial products, however, did not belong to manufactories, the number of which, even by the end of the 17th century, was 100%. did not reach even three dozen, but to peasant household crafts, urban crafts and small commodity production. In connection with the growth of market relations in the country, small-scale commodity production has intensified. Serpukhov, Tula and Tikhvin blacksmiths, Pomeranian carpenters, Yaroslavl weavers and tanners, Moscow furriers and cloth makers worked not so much to order as to the market. Some commodity producers used hired labor, though on a small scale.

Seasonal trades have also been greatly developed, especially in the non-chernozem regions near Moscow and to the north of it. The growth of property and state duties forced the peasants to go to work, to be hired for construction work, for salt and other crafts as auxiliary workers. A large number of peasants were employed in river transport, where barge haulers were required to pull ships up the river, as well as loaders and ship workers. Transport and salt production were served mainly by hired labor. Among the barge haulers and ship workers there were many "walking people", as the documents called people who were not associated with a specific place of residence. In the 17th century, the number of villages and villages inhabited by "non-arable peasants", "non-arable bobs" continuously increased.

Economic regions of Russia

Separate parts of the vast Russian state, which occupied vast areas in Europe and Asia, naturally, were heterogeneous both in terms of natural conditions and in terms of socio-economic development. The most populated and developed was the central region, the so-called Zamoskovny cities with adjacent counties. Villages and villages surrounded the capital from all sides. Moscow was the largest city in Eastern Europe and had up to 200 thousand inhabitants. It was the most important center of trade, handicraft and small commodity production. In it and its environs, first of all, enterprises of the manufactory type arose.

In the central region of Russia, various peasant crafts and urban handicrafts were greatly developed. There were also the largest Russian cities - Yaroslavl, Nizhny Novgorod, Kaluga. A direct land road connected Moscow via Yaroslavl with Vologda, from where the waterway to Arkhangelsk began.

The vast region adjacent to the White Sea, known as Pomorie, was relatively poorly populated at that time. Russians, Karelians, Komi, etc. lived here. In the northern regions of this region, due to climatic conditions, the population was more engaged in crafts (salting, fishing, etc.) than agriculture. The role of Pomerania in supplying the country with salt was especially great. In the area of the largest center of salt production - Kamskaya Salt, there were more than 200 breweries that supplied up to 7 million pounds of salt annually. The most important cities of the North were Vologda and Arkhangelsk, which were the extreme points of the Sukhono-Dvina river route. Trade with foreign countries passed through the port of Arkhangelsk. There were rope workshops in Vologda and Kholmogory. Relatively fertile soils in the region of Vologda, Veliky Ustyug and in the Vyatka region favored the successful development of agriculture. Vologda and Ustyug, and in the second half of the XVII century. Vyatka region were large grain markets.

In the west of Russia there were lands "from German and Lithuanian Ukraine" (outskirts). These were areas that exported flax and hemp to other regions and abroad. The largest cities and trading centers here were Smolensk and Pskov, while Novgorod withered away and lost its former importance.

In the XVII century there was a rapid settlement of the southern regions. Fugitive peasants from the central districts were continuously sent here. The trade and crafts of this region were insignificant, and there were no large cities here, but grain farming successfully developed here on the rich black soil.

Russian peasants also fled to the Middle Volga region. Russian villages arose near Mordovian, Tatar, Chuvash and Mari villages. The lands south of Samara were still sparsely populated. The largest cities in the Volga region were Kazan and Astrakhan. A diverse population lived in Astrakhan: Russians, Tatars, Armenians, people from Bukhara, etc. A lively trade was carried out in this city with the countries of Central Asia, Iran and the Transcaucasus.

In the south of the East European Plain, it was part of Russia in the 17th century. part of the North Caucasus, as well as the regions of the Don and Yaitsk Cossack troops. The wealthy industrialist Guryev founded the city of Guryev with a stone fortress at the mouth of the Yaik (Urals).

After 1654, the Left-bank Ukraine was reunited with Russia along with Kiev, which had self-government and an elected hetman.

By the size of its territory, Russia already in the 17th century was the largest state in the world.

Siberia

The largest region of Russia in the 17th century. was Siberia. It was inhabited by peoples who stood at different levels community development. The most numerous of them were the Yakuts, who occupied a vast territory in the basin of the Lena and its tributaries. The basis of their economy was cattle breeding, hunting and fishing were of secondary importance. In winter, the Yakuts lived in heated wooden yurts, and in the summer they went to pastures. At the head of the Yakut tribes were elders - toyons, owners of large pastures. Among the peoples of the Baikal region, the first place was occupied by the Buryats. Most of the Buryats were engaged in cattle breeding, led a nomadic lifestyle, but there were also agricultural tribes among them. The Buryats were going through a period of the formation of feudal relations, they still had strong patriarchal-tribal remnants.

Evenki (Tungus) lived in the vast expanses from the Yenisei to the Pacific Ocean, engaged in hunting and fishing. Chukchi, Koryaks and Itelmens (Kamchadals) inhabited the northeastern regions of Siberia with the Kamchatka Peninsula. These tribes then sewed in a tribal system; they did not yet know the use of iron.

The expansion of Russian possessions in Siberia was carried out mainly by the local administration and industrial people who were looking for new "lands" rich in fur-bearing animals. Russian industrial people penetrated into Siberia along the high-water Siberian rivers, the tributaries of which come close to each other. Military detachments followed in their footsteps, setting up fortified prisons, which became centers of colonial exploitation of the peoples of Siberia. The path from Western Siberia to Eastern Siberia went along the tributary of the Ob, the Keti River. On the Yenisei, the city of Yeniseisk arose (originally the Yenisei prison, 1619). Somewhat later, another Siberian city, Krasnoyarsk, was founded on the upper reaches of the Yenisei. Along the Angara or the Upper Tunguska, the river route led to the upper reaches of the Lena. The Lensky jail was built on it (1632, later Yakutsk), which became the center of control of Eastern Siberia.

In 1648, Semyon Dezhnev discovered "the edge and end of the Siberian land." The expedition of Fedot Alekseev (Popov), the clerk of the Ustyug trading people, the Usovs, set out to sea from the mouth of the Kolyma, consisting of six ships. Dezhnev was on one of the ships. The storm swept the ships of the expedition, some of them died or were washed ashore, and Dezhnev's ship rounded the extreme northeastern tip of Asia. Thus, Dezhnev was the first to make a sea voyage through the Bering Strait and discovered that Asia was separated from America by water.

By the middle of the XVII century. Russian detachments penetrated into Dauria (Transbaikalia and Amur). The expedition of Vasily Poyarkov along the Zeya and Amur rivers reached the sea. Poyarkov sailed by sea to the Ulya River (Okhotsk region), climbed up it and returned to Yakutsk along the rivers of the Lena basin. A new expedition to the Amur was made by the Cossacks under the command of Yerofey Khabarov, who built a town on the Amur. After the government recalled Khabarov from the town, the Cossacks stayed in it for some time, but due to a lack of food they were forced to leave it.

Penetration into the Amur basin brought Russia into conflict with China. Military operations ended with the conclusion of the Nerchinsk Treaty (1689). The treaty defined the Russian-Chinese border and promoted the development of trade between the two states.

Following industrial and service people, peasant settlers were sent to Siberia. The influx of “free people” into Western Siberia began immediately after the construction of Russian towns and especially intensified in the second half of the 17th century, when “many numbers” of peasants moved here, mainly from the northern and neighboring Ural counties. The arable peasant population settled mainly in Western Siberia, which became the main center of the agricultural economy of this vast region.

Peasants settled on empty lands or seized lands that belonged to local "yasak people". The size of arable plots owned by peasants in the 17th century was not limited. In addition to arable land, it included hay meadows, and sometimes fishing grounds. The Russian peasants brought with them the skills of a higher agricultural culture than that of the Siberian peoples. Rye, oats and barley became the main agricultural crops of Siberia. Along with them, industrial crops appear, primarily hemp. Animal husbandry has been widely developed. Already by the end of the XVII century. Siberian agriculture satisfied the needs of the population of Siberian cities in agricultural products and, thus, freed the government from the expensive delivery of bread from European Russia.

The conquest of Siberia was accompanied by the taxation of the conquered population with yasak - tribute. The payment of yasak was usually made in furs, the most valuable commodity that enriched the royal treasury. The "explaining" of the Siberian peoples by service people was often accompanied by outrageous violence. Official documents admitted that Russian merchants sometimes invited "people to trade and had wives and children from them, and they robbed their stomachs and cattle, and many people did violence to them."

The vast territory of Siberia was under the control of the Siberian order. The intensity of the robbery of the peoples of Siberia by tsarism is evidenced by the fact that the income of the Siberian order in 1680 accounted for more than 12% of the total budget of Russia. The peoples of Siberia, moreover, were subjected to exploitation by Russian merchants, whose wealth was created by exchanging handicrafts and cheap ornaments for fine furs, which constituted an important article of Russian export. The merchants Usovs, Pankratievs, Filatievs and others, having accumulated large capitals in Siberian trade, became owners of manufactories for boiling salt in Pomorye, without stopping their trading activities at the same time. G. Nikitin, a native of the black-haired peasants, at one time worked as a clerk E. Filatiev and for short term moved into the ranks of the Moscow merchant nobility. In 1679, Nikitin was enrolled in the living room hundred, and two years later he was granted the title of guest. By the end of the XVII century. Nikitin's capital exceeded 20 thousand rubles. (about 350 thousand rubles for the money of the beginning of the 20th century). Nikitin, like his former patron Filatiev, made his fortune in the predatory fur trade in Siberia. He was one of the first Russian merchants who organized trade with China.

By the end of the XVII century. significant areas of Western and partly Eastern Siberia were already populated by Russian peasants, who had mastered many previously deserted areas. Most of Siberia became Russian in terms of its population, especially the black earth regions of Western Siberia. Relations with the Russian people, despite the colonial policy of tsarism, were of great importance for the development of the economic and cultural life of all the peoples of Siberia. Under the direct influence of Russian agriculture, the Yakuts and nomadic Buryats began to cultivate arable land. The accession of Siberia to Russia created conditions for the further economic and cultural development of this vast country.

The formation of the all-Russian market

A new phenomenon, exceptional in its significance, was the formation of an all-Russian market, the center of which was Moscow. By the movement of goods to Moscow, one can judge the degree of social and territorial division of labor on the basis of which the all-Russian market was formed: the Moscow region supplied meat and vegetables; cow butter was brought from the Middle Volga region; fish was brought from Pomorye, the Rostov district, the Lower Volga region and the Oka places; vegetables also came from Vereya, Borovsk and Rostov district. Moscow was supplied with iron by Tula, Galich, Ustyuzhna Zhelezopolskaya and Tikhvin; skins were brought mainly from the Yaroslavl-Kostroma and Suzdal regions; wooden utensils were supplied by the Volga region; salt - the cities of Pomorie; Moscow was the largest market for Siberian furs.

Based on the production specialization of individual regions, markets were formed with the primary importance of any goods. So, Yaroslavl was famous for selling leather, soap, lard, meat and textiles; Veliky Ustyug and especially Salt Vychegodskaya were the largest fur markets - furs coming from Siberia were delivered from here either to Arkhangelsk for export, or to Moscow for sale inside the country. Flax and hemp were brought to Smolensk and Pskov from the surrounding areas, which then entered the foreign market.

Some local markets establish intensive trade relations with cities far removed from them. Tikhvin Posad, with its annual fair, supported trade with 45 Russian cities. Buying iron products from local blacksmiths, buyers resold them to larger merchants, and the latter transported significant consignments of goods to Ustyuzhna Zhelezopolskaya, as well as to Moscow, Yaroslavl, Pskov and other cities.

An enormous role in the trade turnover of the country was played by fairs of all-Russian importance, such as Makarievskaya (near Nizhny Novgorod), Svenskaya (near Bryansk), Arkhangelskaya, and others, which lasted for several weeks.

In connection with the formation of the all-Russian market, the role of the merchants in the economic and political life of the country increased. In the 17th century, the top of the merchant world, whose representatives received the title of guests from the government, stood out even more noticeably from the general mass of merchants. These major merchants also played the role of financial agents of the government - on his behalf, they conducted foreign trade in furs, potash, rhubarb, etc., carried out construction contracts, purchased food for the needs of the army, collected taxes, customs duties, tavern money, etc. The guests attracted smaller merchants to carry out contract and farming operations, sharing with them huge profits from the sale of wine and salt. Farming and contracts were an important source of capital accumulation.

Large capitals sometimes accumulated in the hands of individual merchant families. N. Sveteshnikov owned rich salt mines. The Stoyanovs in Novgorod and F. Emelyanov in Pskov were the first people in their cities; their opinion was considered not only by governors, but also by the tsarist government. The guests, as well as merchants close to them in position from the living room and cloth hundreds (associations), were joined by the top of the townspeople, who were called "best", "big" townspeople.

Merchants begin to speak to the government in defense of their interests. In petitions, they asked that English merchants be banned from trading in Moscow and in other cities, with the exception of Arkhangelsk. The petition was satisfied by the tsarist government in 1649. This measure was motivated by political considerations - the fact that the British executed their king Charles I.

Great changes in the country's economy were reflected in the Customs Charter of 1653 and the New Trade Charter of 1667. The head of the Ambassadorial Order, A. L. Ordin-Nashchokin, took part in the creation of the latter. According to the mercantile views of that time, the New Trade Charter noted the special importance of trade for Russia, since “in all neighboring states, in the first state affairs, free and profitable auctions for collecting duties and for the worldly possessions of the world are guarded with all care.” The customs charter of 1653 abolished many small trading fees that had been preserved from the time of feudal fragmentation, and instead of them introduced one so-called ruble duty - 10 kopecks each. from the ruble for the sale of salt, 5 kop. from the ruble from all other goods. In addition, an increased duty was introduced for foreign merchants who sold goods within Russia. In the interests of the Russian merchants, the New Trade Charter of 1667 further increased customs duties from foreign merchants.

2. The beginning of the formation of the feudal-absolutist monarchy

Tsar and Boyar Duma

Great shifts in the economic and social life of the Russian people were accompanied by changes in the political system of Russia. In the 17th century there is a folding in Russia of a feudal-absolutist (autocratic) state. Characteristic for a class-representative monarchy existence next to the royal power. The Boyar Duma and Zemstvo Sobors no longer corresponded to the tendencies to strengthen the dominance of the nobility in the face of a further aggravation of the class struggle. The military and economic expansion of the neighboring states also required a more perfect political organization of the rule of the nobility. The transition to absolutism, which had not yet been completed by the end of the 17th century, was accompanied by the withering away of zemstvo sobors and an ever greater subordination of spiritual authority to secular ones.

Since 1613, the Romanov dynasty reigned in Russia, considering themselves the heirs of the former Moscow tsars through the female line. Mikhail Fedorovich (1613-1645), his son Alexei Mikhailovich (1645-1676), the sons of Alexei Mikhailovich - Fedor Alekseevich (1676-1682), Ivan and Peter Alekseevich (after 1682) reigned successively.

All state affairs in the XVII century. performed in the name of the king. In the "Council Code" of 1649, a special chapter was introduced "On the sovereign's honor and how to protect the state's health", threatening the death penalty for speaking out against the king, governor and clerks "in droves and conspiracy", which meant all mass popular demonstrations. Now the closest royal relatives began to be regarded as the sovereign's "serfs" - subjects. In petitions to the tsar, even noble boyars called themselves diminutive names (Ivashko, Petrushko, etc.). Class distinctions were strictly observed in appeals to the tsar: service people called themselves "serfs", peasants and townspeople - "orphans", and spiritual "pilgrims". The appearance of the tsar on the squares and streets of Moscow was furnished with magnificent solemnity and complex ceremonial, emphasizing the power and inaccessibility of tsarist power.

State affairs were in charge of the Boyar Duma, which also met in the absence of the tsar. The most important cases were dealt with on the royal proposal to "think" about this or that issue; the decision began with the formula: "The king indicated and the boyars were sentenced." The Duma, as the highest legislative and judicial institution, included the most influential and wealthy feudal lords of Russia - members of noble princely families and the closest relatives of the tsar. But along with them, more and more representatives of unborn families penetrated into the Duma - Duma nobles and Duma clerks, who were promoted to high positions in the state thanks to their personal merits. Along with some bureaucratization of the Duma, there was a gradual limitation of its political influence. Next to the Duma, in whose meetings all the Duma ranks took part, there was a Secret, or Near Duma, consisting of the tsar's proxies, who often did not belong to the Duma ranks.

Zemsky Sobors

The government for a long time relied on the support of such an estate-representative institution as the Zemstvo Sobors, resorting to the help of elected people from the nobility and the top of the township society, mainly in the difficult years of the struggle against external enemies and in internal difficulties associated with raising money for urgent needs. Zemsky Sobors functioned almost continuously during the first 10 years of the reign of Mikhail Romanov, for some time gaining the significance of a permanent representative institution under the government. The council that elected Michael to reign (1613) sat for almost three years. The following councils were convened in 1616, 1619 and 1621.

After 1623, there was a long break in the activities of the cathedrals, associated with the strengthening of royal power. The new council was convened in connection with the need to establish extraordinary collections of money from the population, as preparations were made for the war with Poland. This cathedral did not disperse for three years. During the reign of Mikhail Fedorovich, Zemsky Sobors met several more times.

Zemsky Sobors were an institution of a class character and consisted of three "ranks": 1) the higher clergy headed by the patriarch - the "consecrated cathedral", 2) the Boyar Duma and 3) elected from the nobility and from the townspeople. The black-eared peasants, perhaps, participated only in the council of 1613, while the landlords were completely removed from political affairs. Elections of representatives from the nobility and from the townspeople were always made separately. The protocol of the election, the "electoral list", was submitted to Moscow. Voters supplied "elected people" with instructions in which they declared their needs. The council was opened with a royal speech, which spoke about the reasons for its convocation and raised questions for the elected. The discussion of issues was carried out by separate class groups of the cathedral, but the general conciliar decision had to be taken unanimously.

The political authority of the zemstvo sobors, which stood high in the first half of the 17th century, was not durable. The government subsequently reluctantly resorted to convening zemstvo sobors, at which elected people sometimes criticized government measures. The last Zemsky Sobor met in 1653 to resolve the issue of the reunification of Ukraine. After that, the government convened only meetings of individual class groups (service people, merchants, guests, etc.). However, the approval of "the whole earth" was recognized as necessary for the election of sovereigns. Therefore, the meeting of Moscow officials in 1682 twice replaced the Zemsky Sobor - first when Peter was elected to the throne, and then when the two tsars Peter and Ivan were elected, who were supposed to rule jointly.

The zemstvo sobors, as organs of class representation, were abolished by growing absolutism, just as was the case in the countries of Western Europe.

Command system. Governors

The administration of the country was concentrated in numerous orders that were in charge of individual branches of state administration (Ambassadorial, Discharge, Local, Order of the Big Treasury) or regions (Order of the Kazan Palace, Siberian Order). The 17th century was the heyday of the order system: the number of orders in other years reached 50. However, in the second half of the 17th century. in a fragmented and cumbersome command administration, a certain centralization is carried out. Orders related in terms of business were either combined into one or several orders, although they retained their independent existence, they were placed under the general control of one boyar, most often a confidant of the tsar. The associations of the first type include, for example, the combined orders of the palace department: the Grand Palace, the Palace Court, Kamenye Del Konyushenny. An example of the second type of associations is the assignment to the boyar F. A. Golovin to manage the Ambassadorial, Yamsky and Military Naval Orders, as well as the Chambers of the Armory, Gold and Silver Affairs. An important innovation in the order system was the organization of the Order of Secret Affairs, a new institution where "boyars and duma people do not enter and do not know about affairs, except for the tsar himself." This order in relation to other orders performed control functions. The order of secret affairs was arranged so that "the royal thought and deeds would be fulfilled according to his (royal) desire."

The chiefs of most orders were boyars or nobles, but office work was kept on a permanent staff of clerks and their assistants - clerks. Having mastered well the administrative experience passed down from generation to generation, these people ran all the affairs of the orders. At the head of such important orders as Razryadny, Pomesny and Posolsky, there were duma clerks, that is, clerks who had the right to sit in the Boyar Duma. The bureaucratic element became increasingly important in the system of the emerging absolutist state.

The vast territory of the state in the 17th century, as in previous times, was divided into counties. What was new in the organization of local power was the reduction in the importance of the zemstvo administration. Everywhere power was concentrated in the hands of governors sent from Moscow. Assistant governors - "comrades" - were appointed to large cities. Office work was in charge of clerks and clerks. The moving out hut, where the voivode sat, was the center of administration of the county.

The service of the governor, like the old feeding, was considered "mercenary", that is, bringing income. The governor used every excuse to "feed" at the expense of the population. The arrival of the voivode to the territory of the subordinate county was accompanied by the receipt of “entry food”, on holidays they came to him with an offering, a special reward was brought to the voivode during the submission of petitions. The arbitrariness in the local administration was especially felt by the social lower classes.

By 1678, the census of households was completed. After that, the government replaced the existing sosh taxation (sokha - a taxation unit that included from 750 to 1800 acres of cultivated land in three fields) with household taxation. This reform increased the number of taxpayers, taxes were now levied on such segments of the population as "business people" (serfs who worked on the landlords' farm), beans (impoverished peasants), rural artisans, etc., who lived in their yards and had not previously paid taxes . The reform caused the landowners to increase the population in the yards by amalgamating them.

Armed forces

New phenomena are also taking place in the organization of the state's armed forces. The local noble army was completed as a militia from nobles and boyar children. Military service was still compulsory for all nobles. Nobles and boyar children gathered in their counties for a review according to the lists, where all the nobles fit for service were entered, hence the name "service people". Penalties were taken against "netchikov" (who did not show up for service). In summer, noble cavalry usually stood at border cities. In the south, the gathering place was Belgorod.

The mobilization of the local troops was extremely slow, the army was accompanied by huge carts and a large number of landlord servants.

Archers - foot soldiers armed with firearms - were distinguished by a higher combat capability than the noble cavalry. However, the streltsy army by the second half of the 17th century. clearly did not meet the need to have a sufficiently maneuverable and combat-ready army. In peacetime, the archers combined military service with petty trade and crafts, as they received insufficient bread and cash salaries. They were closely associated with the townspeople and took part in the urban unrest of the 17th century.

The need to reorganize the military forces of Russia on new principles was acutely felt already in the first half of the 17th century. Preparing for the war for Smolensk, the government bought weapons from Sweden and Holland, hired foreign military people and began to form Russian regiments of the "new (foreign) system" - soldier's Reiters and Dragoons. The training of these regiments was carried out on the basis of the advanced military art of that time. The regiments were recruited first from "free hunting people", and then from among the "subjective people" recruited from a certain number of peasant and township households. The lifelong service of subordinate people, the introduction of uniform weapons in the form of muskets and flintlock carbines lighter than squeakers gave the regiments of the new system some features of a regular army.

Due to the increase in cash receipts, the cost of maintaining the army has steadily increased.

Strengthening of the nobility

Changes in the state system took place in close connection with a change in the structure of the ruling class of feudal lords, on which the autocracy relied. The top of this class was the boyar aristocracy, who replenished the court ranks (the word "rank" was not yet understood as an official position, but as belonging to a certain group of the population). The Duma ranks were the highest, then the ranks of Moscow followed, followed by the ranks of the city. All of them were included in the category of service people "according to the fatherland", in contrast to the service people "according to the instrument" (archers, gunners, soldiers, etc.). Serving people in the fatherland, or nobles, began to take shape in a closed group with special privileges, inherited. From the middle of the XVII century. the transition of instrumental servicemen to the ranks of the nobility was closed.

Of great importance in eliminating the differences between the individual strata of the ruling class was the abolition of parochialism. Localism had a detrimental effect on the combat capability of the Russian army. Sometimes, just before the battle, the governors, instead of taking decisive action against the enemy, entered into disputes about which of them was higher in “place”. Therefore, according to the decree on the abolition of parochialism, in past years “in many of their state military and embassy, in all sorts of affairs, great dirty tricks and disorganization and destruction were done from those cases, and joy to the enemies, and between them - contrary to God - dislike and great , prolonged feuds. The abolition of localism (1682) increased the importance of the nobility in the state apparatus and the army, since localism prevented the nobility from being promoted to prominent military and administrative posts.

3. Popular uprisings

The position of the peasants and the urban lower classes

The feudal order laid down with all its weight on the broad masses of the people, on the peasants and on the townspeople.

The position of the peasants was difficult not only economically, but also legally. The landlords and their clerks beat the peasants with whips, shackled them in shackles for any offense. The spontaneous manifestation of the struggle of the peasants against the oppressors was the frequent murder of landowners and peasant escapes. The peasants left their homes, hiding in remote and sparsely populated areas in the Volga region and in southern Russia, especially on the Don.

In the city, property and social differences among the townspeople were emphasized by the government itself, which divided the townspeople according to their prosperity into “kind” (or “best”), “middle” and “young”. Most of the townspeople belonged to young people. The best people numbered in the few, but they owned the largest number of trading shops and trade establishments (lard ovens, wax slaughterhouses, distilleries, etc.). They entangled in debt obligations and often ruined young people. Contradictions between the best and youngest townspeople invariably manifested themselves during the elections of zemstvo elders, who were in charge of the distribution of taxes and duties in the township community. Attempts by young people to promote their candidates to zemstvo elders met with a resolute rebuff from the city's wealthy, who accused them of rebellion against the tsarist government. The young townspeople, "looking for the truth" and "from all evil deliverance and from all sorts of violence," burningly hated the city's "world eaters" and took part in all the uprisings of the 17th century.

The feudal state resolutely suppressed any attempt at protest by the dispossessed masses of the people. The scammers immediately reported to the governors and in orders about "unsuitable speeches against the sovereign." The arrested were subjected to torture, which was carried out three times. Those who confessed their guilt were punished with a whip in the square and exile to distant cities, and sometimes even the death penalty. Those who withstood three times of torture were usually released crippled for life. "Izvet" (denunciation) on political matters was legalized in Russia in the 17th century as one of the means of reprisal against popular discontent.

Urban uprisings

Contemporaries called the XVII century "rebellious" time. Indeed, in the previous history of feudal-serf Russia there were not so many anti-feudal uprisings as in the 17th century.

The largest of them in the middle and second half of this century were the urban uprisings of 1648-1650, the "copper riot" of 1662, the peasant war led by Stepan Razin of 1670-1671. A special place is occupied by "split". It began as a religious movement that later found a response among the masses.

Urban uprisings 1648-1650 were directed against the boyars and the government administration, as well as against the tops of the townspeople. Public discontent was intensified by the extreme venality of the state apparatus. Townsmen were forced to give bribes, "promises" to governors and clerks. Craftsmen in the cities were forced to work for free for governors and clerks.

The main driving forces of these uprisings were young townspeople and archers. The uprisings were predominantly urban, but in some areas they also engulfed the countryside.

Unrest in the cities began already in the last years of the reign of Mikhail Romanov, but took the form of uprisings under his son and successor Alexei Mikhailovich. In the first years of his reign, the actual ruler of the state was the royal educator ("uncle") - the boyar Boris Ivanovich Morozov. In his financial policy Morozov relied on merchants, with whom he was closely connected by general trade operations, since his vast estates supplied potash, resin and other products for export abroad. In search of new funds to replenish the royal treasury, the government, on the advice of the Duma clerk N. Chisty, in 1646 replaced direct taxes with a tax on salt, which immediately rose in price almost threefold. It is known that a similar tax (gabel) in France caused in the same XVII century. great popular uprisings.

The hated salt tax was abolished in December 1647, but instead of the revenues received by the treasury from the sale of salt, the government resumed collecting direct taxes - streltsy and yamsky money, demanding their payment in two years.

Unrest began in Moscow in the first days of June 1648. During the procession, a large crowd of townspeople surrounded the tsar and tried to send him a petition complaining about the violence of the boyars and clerks. The guard dispersed the petitioners. But the next day, archers and other military men joined the townspeople. The rebels broke into the Kremlin, in addition, they defeated the courtyards of some boyars, archery chiefs, merchants and clerks. The Duma clerk Chistoy was killed in his house. The rebels forced the government to extradite L. Pleshcheev, who was in charge of the Moscow city administration, and Pleshcheev was publicly executed on the square as a criminal. The rebels demanded that Morozov also be extradited, but the tsar secretly sent him into an honorable exile in one of the northern monasteries. "Posadsky people throughout Moscow", supported by archers and serfs, forced the tsar to go to the square in front of the Kremlin Palace and give an oath promise to fulfill their demands.

The Moscow uprising found a wide response in other cities. There were rumors that in Moscow "the strong are beaten with shards and stones." The uprisings swept a number of northern and southern cities - Veliky Ustyug, Cherdyn, Kozlov, Kursk, Voronezh, etc. In the southern cities, where the townspeople were few, the uprisings were led by archers. They were sometimes joined by peasants from nearby villages. In the North, the main role belonged to the posad people and the black-eared peasants. Thus, already the urban uprisings of 1648 were closely connected with the movement of the peasants. This is also indicated by the petition of the townspeople, submitted to Tsar Alexei during the Moscow uprising: “The whole people in the entire Muscovite state and in its border regions become unsteady from such untruth, as a result of which a great storm rises in your royal capital city of Moscow and in many other places, cities and counties.

The reference to the uprising in frontier places suggests that the rebels may have been aware of the successes of the liberation movement in Ukraine led by Bogdan Khmelnitsky, which began in the spring of the same. 1648

"Code" 1649

The armed uprising of the lower ranks of the city and the archers, which caused confusion in the ruling circles, was used by the nobles and the elite of the merchants to present their estate demands to the government. In numerous petitions, the nobles demanded the issuance of salaries and the abolition of "lesson years" for the investigation of fugitive peasants, guests and merchants sought the introduction of restrictions on the trade of foreigners, as well as the confiscation of privileged urban settlements owned by large secular and spiritual feudal lords. The government was forced to succumb to the harassment of the nobility and the tops of the settlement and convened the Zemsky Sobor to develop a new code of law (code).

At the Zemsky Sobor, convened on September 1, 1648 in Moscow, elected representatives from 121 cities and counties arrived. Provincial nobles (153 people) and townspeople (94 people) ranked first in terms of the number of elected officials. The "Cathedral Code", or a new code of laws, was drawn up by a special commission, discussed by the Zemsky Sobor and printed in 1649 in an exceptionally large circulation of 2,000 copies for that time.

The Code was compiled on the basis of a number of sources, among which we find the Sudebnik of 1550, royal decrees and the Lithuanian Statute. It consisted of 25 chapters divided into articles. The introductory chapter to the "Code" established that "every rank by people, from the highest to the lowest rank, the court and reprisal should be equal in all matters." But this phrase had a purely declarative character, since in reality the Code asserted the estate privileges of the nobles and the tops of the township world. The "Code" confirmed the right of owners to transfer the estate by inheritance, provided that the new landowner would perform military service. In the interests of the nobles, it prohibited the further growth of church land ownership. The peasants were finally assigned to the landowners, and the "lesson summer" for the search for runaway peasants was canceled. The nobles now had the right to search for runaway peasants for an unlimited time. This meant a further strengthening of the serfdom of the peasants from the landlords.

The "Code" forbade the boyars and the clergy to arrange their so-called white settlements in the cities, where their dependent people lived, engaged in trade and craft; all the people who fled from the township tax had to return to the township community again. These articles of the "Code" satisfied the demands of the townspeople, who sought the prohibition of the white settlements, whose population, being engaged in trades and crafts, was not burdened by the township tax and therefore successfully competed with the taxpayers of the black settlements. The liquidation of privately owned settlements was directed against the remnants of feudal fragmentation and strengthened the city.

The "Cathedral Code" became the main legislative code of Russia for more than 180 years, although many of its articles were canceled by further legislative acts.

Uprisings in Pskov and Novgorod

The "Code" not only did not satisfy the broad circles of the townspeople and peasants, but even more deepened the class contradictions. New uprisings in 1650 in Pskov and Novgorod unfolded in the context of the struggle of young townspeople and archers against nobles and large merchants.

The reason for the uprising was grain speculation, which was carried out on the direct orders of the authorities. It was beneficial for the government to raise the price of bread, since the retribution that was taking place at that time with the Swedes for defectors to Russia from the territories that had ceded to Sweden according to the Peace of Stolbov in 1617 was partially made not in money, but in bread at local market prices.

The main part in the Pskov uprising, which began on February 28, 1650, was taken by townspeople and archers. They took the governor into custody and organized their own government in the Zemskaya izba, headed by the baker Gavrila Demidov. On March 15, an uprising broke out in Novgorod, and thus the two large cities refused to obey the tsarist government.

Novgorod lasted no more than a month and submitted to the tsar's governor, Prince I. Khovansky, who immediately imprisoned many participants in the uprising. Pskov continued to fight and successfully repelled the attacks of the tsarist army that approached its walls.

The government of the rebels of Pskov, headed by Gavrila Demidov, took measures to improve the situation of the city's lower classes. The zemstvo hut took into account the food stocks that belonged to the nobles and merchants; young townspeople and archers were placed at the head of the military forces defending the city; executed some nobles caught in relations with the royal troops. The rebels paid special attention to attracting peasants and townspeople in the suburbs to the uprising. Most of the suburbs (Gdov, Ostrov, etc.) joined Pskov. A broad movement began in the countryside, covering a vast territory from Pskov to Novgorod. Detachments of peasants burned the landowners' estates, attacked small detachments of the nobility, disturbed the rear of Khovansky's army. In Moscow itself and other cities it was restless. The population discussed rumors about the Pskov events and expressed their sympathy for the rebellious Pskovites. The government was forced to convene the Zemsky Sobor, which decided to send a delegation of elected people to Pskov. The delegation persuaded the people of Pskov to lay down their arms, promising an amnesty for the rebels. However, this promise was soon broken, and the government sent Demidov, along with other leaders of the uprising, into a distant exile. The Pskov uprising lasted for almost half a year (March - August 1650), and the peasant movement in the Pskov land did not stop for several more years.

"Copper Riot"

A new urban uprising, called the "copper riot", took place in Moscow in 1662. It unfolded in the conditions of economic difficulties caused by the long and devastating war between Russia and the Commonwealth (1654-1667), as well as the war with Sweden. Due to the lack of silver money, the government decided to issue a copper coin, equal in value to silver money. Initially, copper money was accepted willingly (they began to be issued from 1654), but copper cost 20 times cheaper than silver, and copper money was issued in excessive quantities. In addition, "thieves", counterfeit money appeared. They were minted by the moneymakers themselves, who were under the auspices of the royal father-in-law, the boyar Miloslavsky, who was involved in this business.

Copper money gradually began to fall in price; for one silver money they began to give 4, and then 15 copper money. The government itself contributed to the depreciation of copper money, demanding that taxes to the treasury be paid in silver coins, while the salaries of military men were issued in copper. Silver began to disappear from circulation, and this led to a further drop in the value of copper money.

From the introduction of copper money, the townspeople and service people suffered the most according to the device: archers, gunners, etc. Townsmen were obliged to pay cash contributions to the treasury with silver money, and they were paid with copper. “They don’t sell for copper money, there is nowhere to get silver money,” said “anonymous letters” distributed among the population. The peasants refused to sell bread and other provisions for depreciated copper money. Bread prices rose at an incredible rate, despite good harvests.

The dissatisfaction of the townspeople resulted in a great uprising. In the summer of 1662, the townspeople defeated some of the boyar and merchant courts in Moscow. A large crowd went from the city to the village of Kolomenskoye near Moscow, where Tsar Alexei lived at that time, to demand a reduction in taxes and the abolition of copper money. The “quietest” tsar, as the churchmen hypocritically called Alexei, promised to investigate the case of copper money, but immediately treacherously broke his promise. The troops called by him carried out a brutal reprisal against the rebels. About 100 people drowned in the Moskva River during their flight, more than 7 thousand were killed, wounded, or imprisoned. The most severe punishments and torture followed the first massacre.

Peasant war led by Stepan Razin

The most powerful popular uprising of the XVII century. There was a peasant war of 1670-1671. under the leadership of Stepan Razin. It was a direct result of the aggravation of class contradictions in Russia in the second half of the 17th century. The difficult situation of the peasants led to increased escapes to the outskirts. The peasants went to remote places on the Don and in the Volga region, where they hoped to hide from the yoke of landlord exploitation. The Don Cossacks were not socially homogeneous. The "domovity" Cossacks mostly lived in free places along the lower reaches of the Don with its rich fishing grounds. It reluctantly accepted into its composition new aliens, poor (“goofy”) Cossacks. "Golytba" accumulated mainly on the lands along the upper reaches of the Don and its tributaries, but even here the situation of fugitive peasants and serfs was usually difficult, since the thrifty Cossacks forbade them to plow the land, and there were no new fishing places for the newcomers. Golutvenye Cossacks especially suffered from a lack of bread on the Don.

A large number of runaway peasants also settled in the regions of Tambov, Penza, and Simbirsk. Here the peasants founded new villages and villages, plowed up empty lands. But the landowners immediately followed them. They received letters of grant from the tsar for supposedly empty lands; the peasants who settled on these lands again fell into serfdom from the landowners. Walking people concentrated in the cities, who earned their living by odd jobs.

The peoples of the Volga region - Mordovians, Chuvashs, Maris, Tatars - experienced heavy colonial oppression. Russian landowners seized their lands, fishing and hunting grounds. At the same time, state taxes and duties increased.

A large number of people hostile to the feudal state accumulated on the Don and in the Volga region. Among them were many settlers who were exiled to distant Volga cities for participating in uprisings and various kinds of protests against the government and governors. Razin's slogans found a warm response among the Russian peasants and the oppressed peoples of the Volga region.

The beginning of the peasant war was laid on the Don. Golutvenny Cossacks undertook a campaign to the shores of the Crimea and Turkey. But the thrifty Cossacks prevented them from breaking through to the sea, fearing a military clash with the Turks. The Cossacks, led by Ataman Stepan Timofeevich Razin, moved to the Volga and, near Tsaritsyn, captured a caravan of ships heading to Astrakhan. Having sailed freely past Tsaritsyn and Astrakhan, the Cossacks entered the Caspian Sea and headed to the mouth of the Yaik (Ural) River. Razin occupied the Yaitsky town (1667), many Yaitsky Cossacks joined his army. The following year, a detachment of Razin on 24 ships headed for the shores of Iran. Having ravaged the Caspian coast from Derbent to Baku, the Cossacks reached Rasht. During the negotiations, the Persians suddenly attacked them and killed 400 people. In response, the Cossacks defeated the city of Ferahabad. On the way back, at Pig Island, near the mouth of the Kura, the Iranian fleet attacked the Cossack ships, but suffered a complete defeat. The Cossacks returned to Astrakhan and sold the captured booty here.

A successful sea trip to Yaik and to the shores of Iran sharply increased Razin's authority among the population of the Don and the Volga region. Fugitive peasants and serfs, promenading people, the oppressed peoples of the Volga region were only waiting for a signal in order to raise an open uprising against their oppressors. In the spring of 1670, Razin reappeared on the Volga with a 5,000-strong Cossack army. Astrakhan opened the gates for him; Streltsy and townspeople everywhere went over to the side of the Cossacks. At this stage, Razin's movement outgrew the framework of the campaign of 1667-1669. and resulted in a powerful peasant war.

Razin with the main forces went up the Volga. Saratov and Samara met the rebels with bells, bread and salt. But under the fortified Simbirsk, the army lingered for a long time. To the north and west of this city, the peasant war was already raging. A large detachment of rebels under the command of Mikhail Kharitonov took Korsun, Saransk, and captured Penza. Having united with the detachment of Vasily Fedorov, he went to Shatsk. Russian peasants, Mordovians, Chuvashs, Tatars went to war almost without exception, without even waiting for the arrival of Razin's detachments. The peasant war was getting closer and closer to Moscow. Cossack atamans captured Alatyr, Temnikov, Kurmysh. Kozmodemyansk and the fishing village of Lyskovo on the Volga joined the uprising. Cossacks and Lyskovites occupied the fortified Makariev Monastery in the immediate vicinity of Nizhny Novgorod.

On the upper reaches of the Don, the rebels were led by Stepan Razin's brother Frol. The uprising spread to the lands south of Belgorod, inhabited by Ukrainians and bearing the name Sloboda Ukraine. Everywhere the “muzhiks,” as the tsarist documents called the peasants, rose up with weapons in their hands and, together with the oppressed peoples of the Volga region, fought fiercely against the feudal lords. The city of Tsivilsk in Chuvashia was besieged by "Russian people and Chuvash".

The nobles of the Shatsk district complained that they could not get to the royal governors "because of the unsteadiness of the traitorous peasants." In the area of Kadoma, the same "traitor-muzhiks" set up a notch in order to detain the tsarist troops.

Peasant War 1670-1671 covered a large area. The slogans of Razin and his associates raised the oppressed sections of society to fight, the “charming” letters drawn up by the differences called on all “enslaved and disgraced” to put an end to worldly bloodsuckers, to join Razin’s army. According to an eyewitness to the uprising, Razin told the peasants and townspeople in Astrakhan: “For the cause, brothers. Now take revenge on the tyrants who have hitherto kept you in captivity worse than the Turks or the pagans. I have come to give you freedom and deliverance."

The Don and Zaporozhye Cossacks, peasants and serfs, young townspeople, service people, Mordovians, Chuvashs, Maris, Tatars joined the ranks of the rebels. All of them were united by a common goal - the struggle against feudal oppression. In the cities that went over to the side of Razin, the voivodship power was destroyed and the management of the city passed into the hands of the elected. However, fighting against feudal oppression, the rebels remained tsarist. They stood for the “good king” and spread the rumor that Tsarevich Alexei was with them, who at that time in reality was no longer alive.

The peasant war forced the tsarist government to mobilize all its forces to suppress it. Near Moscow, for 8 days, a review of the 60,000th noble army was carried out. In Moscow itself, a strict police regime was established, as they were afraid of unrest among the city's lower classes.

A decisive clash between the rebels and the tsarist troops took place near Simbirsk. Large reinforcements from the Tatars, Chuvashs and Mordovians flocked to the detachments to Razin, but the siege of the city dragged on for a whole month, and this allowed the tsarist governors to gather large forces. Near Simbirsk, Razin's troops were defeated by regiments of a foreign system (October 1670). Expecting to recruit a new army, Razin went to the Don, but there he was treacherously captured by thrifty Cossacks and taken to Moscow, where he was subjected to a painful execution in June 1671 - quartering. But the uprising continued even after his death. Astrakhan held out the longest. She surrendered to the tsarist troops only at the end of 1671.

Split

The fierce class struggle that unfolded in Russia in the second half of the 17th century was also reflected in such a social movement as the schism of the Orthodox Church. Bourgeois historians emphasized only the ecclesiastical side of the schism and therefore focused their main attention on the ritual disagreements between the Old Believers and the ruling church. In fact, the split also reflected class contradictions in Russian society. It was not only a religious, but also a social movement, which clothed class interests and demands in a religious shell.

The reason for the split of the Russian Church was the disagreement on the issue of correcting church rites and books. Translations of church books into Russian were made from Greek originals at different times, and the originals themselves were not exactly the same, and the scribes of the books additionally made changes and distortions to them. In addition, rituals that were not known in the Greek and South Slavic lands were established in Russian church practice.

The question of correcting church books and rituals became especially acute after Nikon was appointed to the patriarchate. The new patriarch, the son of a peasant from the vicinity of Nizhny Novgorod, who took the monastic vows under the name of Nikon, quickly advanced in church circles. Elevated to the patriarchy (1652), he took the position of the first person in the state after the king. The tsar called Nikon his "common friend".

Nikon energetically set about correcting liturgical books and rites, seeking to bring Russian church practice into line with Greek. The government supported Nikon's undertakings, since the introduction of the uniformity of church services and the strengthening of the centralization of church administration corresponded to the interests of absolutism. But the theocratic ideas of Nikon, who compared the power of the patriarch with the sun, and the power of the king with the moon, only reflected sunlight, contradicted the growing absolutism. For several years, Nikon imperiously interfered in secular affairs. These contradictions led to a quarrel between the tsar and Nikon, which ended in the deposition of the ambitious patriarch. The Council of 1666 deprived Nikon of his patriarchal rank, but at the same time approved his innovations and anathematized those who refused to accept them.

From this council begins the division of the Russian Church into the dominant Orthodox and the Orthodox Old Believers, that is, rejecting Nikon's church reforms. Both churches equally considered themselves the only Orthodox; the official church called the Old Believers "schismatics", the Old Believers called the Orthodox "Nikonians". The schismatic movement was led by Archpriest Avvakum Petrovich, also from Nizhny Novgorod, a man with the same indomitable and domineering nature as Nikon himself. “We see that winter wants to be; my heart went cold and my legs trembled,” wrote Avvakum later about correcting church books.

After the council of 1666, the supporters of the schism were persecuted. However, it was not easy to deal with the split, as it found support among the peasants and townspeople. Theological disputes were little accessible to them, but the old was their own, familiar, and the new was forcibly imposed by the feudal state and the church supporting it.

The Solovetsky Monastery offered open resistance to the tsarist troops. Located on the islands of the White Sea, this richest of the northern monasteries was at the same time a strong fortress, was protected stone walls, had a considerable number of guns and food stocks for many years. The monks who stood for an agreement with the tsarist government were removed from the management of the monastery; power was taken over by the archers, exiled to the North, differences and working people. Under the influence of the peasant war taking place at that time, led by Razin, the Solovetsky uprising, arising on the basis of a split, turned into an open anti-feudal movement. The siege of the Solovetsky Monastery lasted eight years (1668-1676). The monastery was taken only as a result of treason.

The growing oppression of the feudal state led to the further development of the split, despite the most severe government persecution. Archpriest Avvakum, after a tedious stay in an earthen prison, was burned in 1682 in Pustozersk at the stake, and by his death further strengthened the "old faith." The Old Believers fled to the outskirts of the state, to dense forests and swamps. However, religious ideology gave this movement a reactionary character. Among its participants, the savage doctrine of the imminent end of the world and the need for self-immolation began to spread in order to avoid the "anti-Christ" power. At the end of the XVII century. self-immolation became a common occurrence in the north of Rus'.

4. Russia's international position

Russia was greatly weakened by the prolonged Polish-Swedish intervention and lost large and economically important territories in the west. Especially hard was the loss of Smolensk and the coast of the Gulf of Finland, as a direct outlet to the Baltic Sea. The return of these original Russian territories, which were of great importance for the entire economic life of the country, remained the direct task of Russia's foreign policy in the 17th century. An equally important task was to fight for the reunification of the Ukrainian and Belarusian lands within the framework of a single Russian state, as well as to defend the southern borders from the Crimean raids and the aggressive campaigns of the Turks.

"Azov seat". Zemsky Sobor in 1642

The unsuccessful outcome of the Smolensk war complicated the international position of Russia. The situation on the southern outskirts of the country, which was constantly devastated by the predatory raids of the Crimean Tatars, was especially alarming. Only in the first half of the XVII century. the Crimean Tatars, who were in vassal dependence on Turkey, took up to 200 thousand Russian people to the “full”. To protect the southern borders, the Russian government in the 30s of the XVII century. began the repair and construction of new defensive structures - the so-called notch lines, which consisted of notches, ditches, ramparts and fortified towns, stretching in a narrow chain along the southern borders. The defensive lines made it difficult for the Crimeans to reach the inner districts of Russia, but their construction cost the Russian people enormous efforts.

Two Turkish fortresses stood at the mouth of the largest southern rivers: Ochakov - at the confluence of the Dnieper and Bug into the sea, Azov - at the confluence of the Don into the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov. And although there were no Turkish settlements in the Don basin, the Turks held Azov as the base of their possessions in the Black Sea and the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov .

Meanwhile, in the first half of the XVII century. Russian settlements on the Don reached almost to Azov. The Don Cossacks grew into a large military force and usually acted in alliance with the Cossacks against Turkish troops and Crimean Tatars. Often, light Cossack ships, having deceived the Turkish guards near Azov, broke through the Don branches into the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov. From here, the Cossack fleet headed for the shores of the Crimea and Asia Minor, making raids on the Crimean and Turkish cities. For the Turks, the Cossack campaigns against Kafa (present-day Feodosia) and Sinop (in Asia Minor) were especially memorable, when these largest Black Sea cities were devastated. Wishing to prevent the Cossack fleet from penetrating into the Sea of Azov, the Turkish government kept a military squadron at the mouth of the Don, but the Cossack naval boats with a team of 40-50 people nevertheless successfully broke through the Turkish barriers into the Black Sea.

In 1637, taking advantage of the internal and external difficulties of the Ottoman Empire, the Cossacks approached Azov and took it after an eight-week siege. This was not a sudden raid, but a real regular siege with the use of artillery and the organization of earthworks. According to the Cossacks, they “crushed many towers and walls with cannons. And they dug in ... near the whole hail, and the tunnel was let down.

The loss of Azov was extremely sensitive for Turkey, which, thus, was deprived of its most important fortress in the Sea of \u200b\u200bAzov. However, the main Turkish forces were distracted by the war with Iran, and the Turkish expedition against Azov could take place only in 1641. The Turkish army sent to besiege Azov many times exceeded the Cossack garrison in the city, had siege artillery and was supported by a powerful fleet. The besieged Cossacks fought fiercely. They repelled 24 Turkish attacks, inflicted enormous damage on the Turks and forced them to lift the siege. Nevertheless, the issue of Azov was not resolved, because Turkey did not want to give up this important fortress on the banks of the Don. Since the Cossacks alone could not defend Azov against overwhelming Turkish forces, the question arose before the Russian government whether to wage war for Azov or abandon it.

To resolve the issue of Azov in Moscow, the Zemsky Sobor was convened in 1642. The elected people unanimously proposed leaving Azov to Russia, but at the same time they complained about their difficult situation. The nobles accused the clerks of extortion during the distribution of estates and money, the townspeople complained about heavy duties and cash payments. Rumors circulated in the provinces of an imminent "distemper" in Moscow and a general uprising against the boyars. The situation within the state was so alarming that it was impossible even to think of a new, hard, protracted war. The government refused to further protect Azov and invited the Don Cossacks to leave the city. The Cossacks left the fortress, ruining it to the ground. The defense of Azov was sung for a long time in folk songs, in prosaic and poetic stories. One of these stories ends with the words, as if summing up the heroic struggle for Azov: "There was eternal glory to the Cossacks, and eternal reproach to the Turks."

War with Poland for Ukraine and Belarus

The largest foreign policy event of the 17th century, in which Russia took part, was the long war of 1654-1667. This war, which began as a war between Russia and the Commonwealth for Ukraine and Belarus, soon turned into a major international conflict, in which Sweden, the Ottoman Empire and its vassal states - Moldavia and the Crimean Khanate took part. In terms of its significance for Eastern Europe, the war of 1654-1667. can be put on a par with the Thirty Years' War.

Hostilities began in the spring of 1654. Part of the Russian troops were sent to Ukraine for joint operations with the army of Bogdan Khmelnitsky against the Crimean Tatars and Poland. The Russian command concentrated its main forces on the Belarusian theater, where it was supposed to inflict decisive blows on the troops of the gentry of Poland. The beginning of the war was marked by great successes of the Russian troops. In less than two years (1654-1655), Russian troops captured Smolensk and important cities of Belarus and Lithuania: Mogilev, Vitebsk, Minsk, Vilna (Vilnius), Kovno (Kaunas) and Grodno. Everywhere Russian troops found the support of Russian and Belarusian peasants and the urban population. Even official Polish sources admitted that wherever the Russians came, “muzhiks gather in droves” everywhere. In the cities, artisans and merchants refused to oppose the Russian troops. Peasant detachments smashed the pan's estates. Military successes in Belarus were achieved with the support of Ukrainian Cossack detachments.

Significant success was also achieved by Russian troops and Khmelnitsky's detachments operating in Ukraine. In the summer of 1655 they moved west and during the autumn they liberated the western Ukrainian lands up to Lvov from the Polish-gentry oppression.

Russia's war with Sweden

The weakening of the Commonwealth prompted the Swedish king Charles X Gustav to declare war on it under an insignificant pretext. Encountering weak resistance, the Swedish troops occupied almost all of Poland, together with its capital Warsaw, as well as part of Lithuania and Belarus, where the Swedes were supported by the largest Lithuanian magnate Janusz Radziwill. The intervention of Sweden dramatically changed the balance of power in Eastern Europe. Easy victories in Poland significantly strengthened the position of Sweden, which established itself on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Considering that the Polish army had lost its combat capability for a long time, the Russian government concluded a truce with Poland in Vilna and started a war against Sweden (1656-1658).

In this war, the issue of obtaining access to the Baltic Sea by Russia was of great importance. Russian troops took Koknese (Kokenhausen) on the Western Dvina and began the siege of Riga. At the same time, another Russian detachment took Nyenschantz on the Neva and laid siege to Noteburg (Oreshek).

The war between Russia and Sweden diverted the main forces of both states from the Commonwealth, where a broad popular movement began against the Swedish invaders, which led to the cleansing of Polish territory from Swedish troops. The government of the Polish King Jan Casimir, not wanting to put up with the loss of Ukrainian and Belarusian lands, resumed the fight against Russia. At the cost of territorial concessions, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1660 concluded the Peace of Oliva with Sweden, which made it possible to throw all the armed forces against the Russian troops. This prompted the Moscow government to first conclude a truce, and then peace with Sweden (the Peace of Cardis in 1661). Russia was forced to abandon all its acquisitions received in the Baltic states during the Russo-Swedish war.

Andrusovo truce of 1667

The hostilities resumed in 1659 developed unfavorably for the Russian troops, who left Minsk, Borisov and Mogilev. In Ukraine, the Russian army was defeated by the Polish-Crimean forces near Chudnov. Soon, however, the advance of the Poles was suspended. A protracted war began, exhausting the forces of both sides.