The tragedy of the Russian people lies in the fact that at the beginning of the 20th century, with a colossal economic upsurge, foreign special services managed to ruin the country in the blink of an eye - in just a week. It is worth recognizing that the processes of decay, pardon the expression, of the "mass of the people" (both the elite and the common people) have been going on for quite a long time - about 20, or even more, years. There was no great autocrat Alexander III, Father John of Kronstadt passed away (whose portrait hung in every house in Russia), Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin was killed on the 11th attempt, the British agent Oswald Raynor fired the last bullet in the head of Grigory Rasputin - and there was no great country, whose name only remained in our souls, hearts and in the title.

With all the greatness and prosperity, our then elite played too much with their foreign friends, forgetting that each country should take into account only its own personal, purely mercantile interest in international politics. So it turned out that after the defeat of Napoleon in the Patriotic War of 1812, under the guise of secret societies, representatives of the British (and under her knowledge - and French) intelligence poured in to us, who began to "spud" fragile young minds, replacing in their minds the Russian age-old "For Faith! For the King! For the Fatherland! to "Freedom! Equality! Brotherhood!". But today we already know that the results of political insinuations did not smell of either one or the other, or the third. Following in the footsteps of the "Great French", the foreign rulers of thoughts, through the hands of the Russian people, shed so much blood that these memories are not easy for us to this day.

One of the books that fell into my hands is dedicated to the role of secret societies in revolutionary movements and upheavals in Russia - from Peter I to the death of the Russian Empire. It belongs to the pen of Vasily Fedorovich Ivanov and is called "Russian Intelligentsia and Freemasonry." I bring to your attention a quote from this book, which clearly proves why the people loved Alexander III so much - not only for his will, but also for his phenomenal economic performance.

So, I quote the above book pp. 20-22:

“From 1881 to 1917, Russia victoriously advanced in its economic and cultural development, as evidenced by well-known figures.

Shaken by the Crimean campaign of 1853-1856, Russian finances were in a very difficult position. The Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, which demanded enormous extraordinary expenses, upset our finances even more. Large budget deficits have therefore become a constant annual phenomenon. Credit fell more and more. It got to the point that five percent funds in 1881 were valued at only 89 to 93 per 100 of their nominal value, and five percent bonds of city credit societies and mortgage bonds of land banks were already quoted only 80 to 85 per 100.

Through reasonable cost savings, the government of Emperor Alexander III achieved a restoration of budgetary equilibrium, and then large annual surpluses of revenues over expenditures followed. The direction of the received savings to economic enterprises that contributed to the rise of economic activity, to the development of the railway network and the construction of ports led to the development of industry and streamlined both domestic and international exchange of goods, which opened up new sources of increasing state revenues.

For example, let us compare, for example, the data for 1881 and 1894 on the capitals of joint-stock commercial credit banks. Here is the data in thousands of rubles:

It turns out, therefore, that the capital belonging to the banks increased by 59% in just thirteen years, and the balance of their operations rose from 404,405,000 rubles by 1881 to 800,947,000 rubles by 1894, i.e., increased by 98%, or almost double.

No less success was found in institutions mortgage loan. By January 1, 1881, they issued mortgage bonds for 904,743,000 rubles, and by July 1, 1894 - already for 1,708,805,975 rubles, and the rate of these interest-bearing securities increased by more than 10%.

Taken separately, the accounting and loan operation of the State Bank, which reached 211,500,000 rubles by March 1, 1887, increased by October 1 of this year to 292,300,000 rubles, an increase of 38%.

The construction of railways in Russia, which had been suspended at the end of the seventies, resumed with the accession of Alexander III and went on at a rapid and successful pace. But most important in this regard was the establishment of the influence of the government in the field of railways, both by expanding the state-owned operation of railroads, and - in particular - by subordinating the activities of private companies to government supervision. The length of railways open for traffic (in versts) was:

| By January 1, 1881 | By 1 Sept. 1894 | |

| State | 164.6 | 18.776 |

| Private | 21.064,8 | 14.389 |

| Total: | 21.229,4 | 33.165 |

The customs taxation of foreign goods, which in 1880 amounted to 10.5 metal, kopecks. from one ruble of value, increased in 1893 to 20.25 metal, kopecks, or almost doubled. The beneficial effect on the turnover of Russia's foreign trade was not slow to lead to results important in the state relation: our annual large surcharges to foreigners were replaced by even more significant receipts from them, as the following data (in thousands of rubles) testify:

The reduction in the import of foreign goods to Russia was naturally accompanied by the development of national production. The annual production of factories and plants, which are in charge of the Ministry of Finance, was estimated in 1879 at 829,100,000 rubles with 627,000 workers. In 1890, the cost of production increased to 1,263,964,000 rubles with 852,726 workers. Thus, over the course of eleven years, the cost of factory output increased by 52.5%, or more than one and a half times.

Particularly brilliant, in some branches directly astonishing successes have been achieved by the mining industry, as can be seen from the following report on the production of the main products (in thousands of poods):

Emperor Alexander III At the same time, he tirelessly cared about the well-being of the working people. The law of July 1, 1882 greatly facilitated the employment of juveniles in factory production: on June 3, 1885, night work of women and adolescents in factories of fibrous substances was prohibited. In 1886, a regulation on hiring for rural work and a decree on hiring workers for factories and factories were issued, then supplemented and expanded. In 1885, the provision on the cash desks of mining associations, approved in 1881, was changed by establishing a shorter period of length of service for miners' pensions.

Despite the extremely difficult state of public finances at that time, the law of December 28, 1881 significantly reduced redemption payments, and the law of May 28, 1885 stopped the collection of the poll tax.

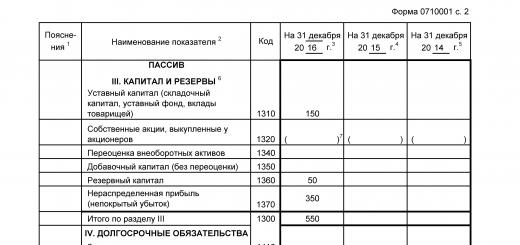

All these concerns of the late autocrat were crowned with brilliant success. Not only were the difficulties inherited from the past era eliminated, but the state economy in the reign of Alexander III achieved a high degree of success, as evidenced, among other things, by the following data on the execution of the state budget (in rubles):

| In 1880 | In 1893 | |

| Income | 651.016.683 | 1.045.685.472 |

| Expenses | 695.549.392 | 946.955.017 |

| Total: | — 44.532.709 | +98.730.455 |

Let government spending increase in 1893 against 1880 by 36.2%, but at the same time revenues increased by 60.6%, as a result of the execution of the painting, instead of the deficit of 44,532,709 rubles that was in 1880, now there is an excess of revenues over expenditures at 98,730,455 rubles. The extraordinarily rapid growth of state revenues did not decrease, but increased the accumulation of savings by the people.

The amount of deposits in savings banks, determined in 1881 at 9,995,225 rubles, increases by August 1, 1894 to 329,064,748 rubles. In some thirteen and a half years, the people's savings went from 10 million to 330, i.e. increased by 33 times.

IN reign of Emperor Nicholas II Russia has achieved even greater success economically and culturally.

The anarchist wave of the “liberation movement” that had arisen in 1905 was swept away by the firm hand of the great Russian man P. A. Stolypin and the efforts of Russian patriots who united at the throne in the name of saving their native land. Historical words of P. A. Stolypin: “Do not intimidate. You need great upheavals, but we need a great Russia" - spread around the world and aroused enthusiasm among the Russian people. "

After the era of the "Great Reforms" 1860-1870. the country entered the next period of its history, which received "castre reforms". Under Alexander III, many of the reforms carried out by the government of his father not only did not receive further development, but were seriously curtailed, and some were directly canceled. The "Temporary Rules on the Press" (1882) were introduced, establishing strict administrative control over newspapers and magazines. In 1887, a circular was published on "cook's children", according to which the Axis forbade the children of coachmen, lackeys, laundresses, small shopkeepers, etc. to be admitted to the gymnasium. In 1884, the autonomy of the universities was actually abolished. In 1889, the "Regulations on zemstvo district chiefs" were issued, according to which zemstvo chiefs were charged with the duty to exercise control over the activities of peasant and volost institutions. In accordance with various documents of the 1880s-1890s, the elective representation of peasants in provincial and district zemstvo institutions was sharply reduced, and the voting rights of the urban population were curtailed by raising the property qualification. In the same years, an attempt was made to limit the judicial reform of 1864-1870.

The main feature of the life of post-reform Russia was the rapid development of the market economy. Although this process originated in the depths of serfdom, it was the reforms of the 1860s and 1870s that opened a wide avenue for new socio-economic relations and allowed them to establish themselves in the economy as the dominant system. The "great reforms" of Alexander II made it possible to break feudal relations in the entire national economy, to complete the industrial revolution. Form new social groups characteristic of a market economy.

This transitional process was complicated by the presence of a still backward political system - absolutist autocracy and the class structure of society, which led to controversial and painful events at the turn of the century.

The remnants of serfdom that remained after 1861 hindered the development of market relations in agriculture. Huge redemption payments were a heavy burden on millions of peasants. In addition, instead of the landowner's power in the countryside, the oppression of the community was strengthened, which could impose a fine on hard-working peasants for their work, and on holidays sentence the peasants to exile in Siberia "for witchcraft", etc. Many peasants experienced great hardships due to the fact that they could not freely dispose of their allotment (sell, bequeath, mortgage in the Peasant Bank), and also run their household as they saw fit. In many communities, redistribution of land was carried out, which excluded the interest of the peasants in increasing soil fertility (for example, fertilizing the fields), since after a while the plots had to be transferred to others. Often, compulsory crop rotation was established in the communities, the peasants were charged with the obligation to simultaneously start and finish field work. As a result of all this, the rise of agriculture proceeded slowly and with great difficulty.

And yet, in the 1880s and 1890s, market relations penetrated into the agricultural sector. This was noticeable in several ways: there was a social differentiation of the peasant population, the essence of the landlord economy was changing, and the orientation of specialized farms and regions to the market increased.

Zemstvo statistics already in the 1880s showed a significant property stratification of the peasants. First of all, a layer of wealthy peasants was formed, whose farms consisted of their own allotments and allotments of impoverished community members. The kulaks stood out from this stratum, they ran an entrepreneurial economy, using hired laborers, sent a large volume of products to the market and thereby increased the degree of marketability of their production. But this group of peasants was still small.

The poor part of the peasantry, having their own economy, often combined agriculture with various crafts. From this stratum, a group of "spread" households stood out, which gradually lost their economic independence, leaving for the city or hiring as farm laborers. By the way, it was this group that created the labor market for both kulaks and industrialists. At the same time, this part of the peasants, receiving payment for their work, also began to show a certain demand for consumer goods.

Formation of a layer of the prosperous. peasants created a steady demand for agricultural machinery, fertilizers, seeds and thoroughbred livestock, which also influenced the country's market economy, since an increase in demand led to the development of various industries.

Significant changes also took place in the landowners' farms, which gradually made the transition from patriarchal forms to market relations. In the 1870s and 1880s, former serfs still kept working off their own plots. These peasants cultivated the landlords' lands with their tools for the right to rent arable and other lands, but they already acted as legally free people with whom it was necessary to enter into relations based on the laws of the market.

The landlords could no longer force the peasants to work in their fields as before. Wealthy peasants sought to quickly redeem their own plots, so as not to work off the segments that arose after 1861. The “peasants” did not at all want to work out a ransom, since they were not kept in the village by insignificant plots of land and it was more profitable for them to go to the city or get hired in strong kulak farms for a higher pay, without any bondage.

In order to turn their estates into profitable farms, the landlords needed new machines, seeds, fertilizers, new agricultural techniques, and all this required significant capital and qualified managers. But not all landlords were able to adapt to new methods of management, so many of them were forced to mortgage and re-mortgage their estates in credit institutions, or even simply sell them. Increasingly, former serfs, and now wealthy peasants, became their buyers.

In post-reform agriculture, its commodity character was more and more clearly visible. At the same time, the market turnover included not only agricultural products, but also land, free labor. The previously outlined regional specialization in the production of marketable grain, flax, sugar beets, oilseeds, and livestock products took shape more clearly, which also contributed to market exchange between the regions.

In addition to traditional organizational forms, in the southern Russian steppes and in Ukraine, large economy estates began to appear, which numbered several thousand acres of land and which were already oriented to the market, primarily foreign. Economy farms were based on a good technical base and hired labor. Thanks to these changes, the level of agricultural production in Russia has increased markedly. In the 1860s-1890s, grain harvests increased 1.7 times, potatoes - 2.5 times, beet sugar production - 20 times.

But despite these achievements, late XIX century, the agrarian issue in Russia remained very acute, since the reform of 1861 was not brought to its logical conclusion. The peasant shortage of land increased sharply, as the number of rural population in 1861-1899 increased from 24 million to 44 million souls of a male goal, and the size of allotment land use per capita of a male decreased on average from 5 to 2.7 acres. They had to rent land on extortionate terms or buy it at a high price.

Along with chronic lack of land, the peasants experienced a huge tax burden. During the reform era, the peasants paid about 89 million gold rubles in the form of taxes and redemption payments. annually. Of the total amount of taxes received by the treasury from the rural population, 94% was levied on peasant farms, and only 6% - on landlords.

Agriculture was backward both technically and agronomically, which affected both the general economic situation of the country and social tension, since the rural population reached 85% of its total number. Low yields gave rise to periodic food shortages in the country. The extremely difficult situation of the peasants was aggravated by several lean years in a row, which led to the catastrophic famine of 1891, which affected more than 40 million people.

In the 1880s of the 19th century, the industrial revolution was largely completed.

In the leading sectors of the national economy, steam engines and a variety of machinery began to predominate - machine tools, equipment, mechanisms, primarily in the manufacturing industry. So, from 1875 to 1892, the number of steam engines in Russia doubled, and their power tripled. During the last decades of the 19th century, new industries appeared and began to develop rapidly: coal, oil production and oil refining, mechanical engineering, chemical production, etc.

Traditional industrial areas in the Center, in the Urals and in the Baltic States were supplemented by new ones: coal and metallurgical in the Donbass and Krivoy Rog. Large industrial centers grew up: Yuzovka, Gorlovka, Narva, Orekhovo-Zuevo, Izhevsk, etc. Cast iron production moved from the Urals to the south of Russia. Large machine-building plants for the production of steam locomotives (Kolomna), steamboats (Sormovo), agricultural machinery (Kharkov, Odessa, Berdyansk) appeared.

In the 1890s, the number of steam locomotives produced doubled compared to the 1870s, which made it possible to completely abandon their import from abroad. During the 30 post-reform years, such large machine-building enterprises as the Nobel mechanical plant, the Obukhovsky steel and cannon plant in St. Petersburg, the mechanical plant in Perm, etc. were built.

In the south of the country, advanced metallurgical plants were built. In 1872, the first blast furnace was put into operation in Yuzovka (at the plant of the English industrialist J. Hughes), two years later - at the Sulinsky Metallurgical Plant. A few years later, the Yuzovsky and Sulinsky plants switched to rich ore from Krivoy Rog, which led to a rapid rise in ferrous metallurgy in this region.

Soon they were joined by a metallurgical region with a center in Yekaterinoslav. The young southern metallurgy, which grew up on a free, and not on a serf labor force, turned into the main industrial base of the country. By the beginning of the 1890s, more than 20% of all Russian pig iron was produced here, and by the end of the century -. 62%. Over 65% of the total Russian volume of coal was mined in the Donbass. Coal has become the most important energy source for all industry and transport.

Among the new industries, oil production and oil refining developed most rapidly, primarily in the Baku region. Initially, there was a system of paying off oil wells for a certain period. Since 1872, the oil regions began to be leased for long-term auctions. At the same time, a new technique began to be introduced - drilling wells and pumping oil using steam engines. All this made it possible to increase oil production in the 1870-1890s from 1.7 million to 243 million poods, i.e. 140 times. By the end of the 19th century, oil production increased to 633 million poods, which allowed Russia to take first place in the world in this indicator. Of the petroleum products, kerosene for domestic consumption began to be in great demand. Fuel oil and gasoline have been used in industry and transport in small quantities so far.

A feature of this period was the rapid development of scattered manufactory, when part of the manufacturing industry "moved" to the countryside, where there were cheap laborers. The peasants, still attached to communal plots, widely participated in various crafts, from which large industrial enterprises were later created. Thus, numerous factory settlements arose in Central Russia - Orekhovo-Zuevo, Pavlovsky Posad, Gus Khrustalny, etc., in which up to 50% of industrial workers lived at the end of the 19th century. Along with large industrial centers in the depths of Russia, new types of small industry developed, which were connected with large factories by the division of labor.

Significant changes were also taking place in the labor market. If in pre-reform Russia workers of industrial enterprises were most often quitrent serfs or serfs of sessional and patrimonial manufactories, then in the 1860s and 1870s they became free people, not connected with the community, who permanently moved to the cities with their families.

They differed markedly from the previous workers in a higher level of literacy, since work in industrial enterprises required them to be able to service various machines and equipment. Qualified personnel were especially needed in large factories and in railway transport. Their number for 1865-1890 increased from 706 thousand to 1432 thousand people.

The urban population grew at an especially rapid pace at the expense of peasants in the 1890s, when the work of temporarily obliged peasants was basically completed, and they could freely go to the cities to earn money. So, if in the early 1860s about 1.3 million people a year left with passports, then in the 1890s - over 7 million people.

According to official statistics of the end of the century, the urban population consisted of the following groups: the big bourgeoisie, landlords and senior officials - 11%, small artisans and shopkeepers - 24%, "working people" - 52%.

A major role in the post-reform economy began to play rail transport, which became an important element of the entire infrastructure. Railways linked Central Russia and its outskirts into a single economic mechanism, contributed to the formation of a market economy, and increased the mobility of the population. During the second half of the 19th century, Russia built railways much faster than many Western European countries. During 1861-1891 their length increased from 1.5 thousand to 28 thousand versts. In 1865-1875, 1.5 thousand miles were built annually in the country. By 1899, the railways already totaled 58 thousand miles.

The railroads were supposed to firmly connect the center of the country with large grain regions. This was served by such lines as Moscow - Kursk, Moscow Voronezh, Moscow Nizhny Novgorod. New lines were laid to seaports on the Baltic and Black Seas - to Odessa, Riga, Libava (Liepaja), from where grain and other agricultural products were exported abroad. Since the late 1870s, the construction of industrial roads began. Highways were laid in industrial areas: in the Donbass, Krivoy Rog, to the Urals. The Transcaucasian road Baku - Tiflis - Batumi ensured the transportation of oil to the Black Sea port.

The industrial boom of the 1890s was marked by the booming growth of the railroads. Over ten years, more than 21,000 miles of railways were built, or a third of all roads in Russia. In the 1890s, the Trans-Siberian Railway was laid with a length of 6 thousand miles, the construction of which began in 1886. In terms of the length of railways, Russia has taken second place in the world after the United States. Gradually, the railways were interconnected at large junctions, creating a single railway system in the European part of the country. However, the railway network in terms of 1 thousand square meters. km of territory was very small compared to the advanced countries.

Initially, railways were built mainly with private funds with wide involvement. foreign capital. Gradually, more and more public funds were invested here, thereby merging private capital with the state. State orders for the construction of railways often turned into gratuitous subsidies. The rapid development of railways was under the protection of the state, which entailed strong state intervention in the economy as a whole. In the mid-1880s, the state began to generally buy roads from private companies, and build new ones at the expense of the treasury.

Railways, presenting a huge demand for metal, coal, timber, oil, etc., served as a powerful stimulus for the development of various industries. Thus, in the 1890s, railways consumed up to 36% of the coal produced in the country, 40% of oil, and 40% of metal. The railways required qualified workers: machinists, depot workers and track facilities.

Along with the railway, water transport has also received great development. If in 1860 there were about 400 river steamers in Russia, then in the 1890s - over 1.5 thousand. Russia, which practically did not have its own navy in the middle of the 19th century and used foreign ships for transportation, increased them over the last decades of the century quantity from 50 to 520.

The domestic market has noticeably changed. The post-reform years were marked by a rapid growth in domestic trade: in 1873-1900 from 2.4 billion to almost 12 billion rubles. With the general development of large-scale industry and railway transport the forms of trade also changed. Seasonal fairs persisted mainly in the less developed regions. In large cities, trading companies were created with an extensive network of stationary stores and warehouses. Commodity exchanges were formed with a huge trade turnover. As a rule, the exchanges functioned on a specialized basis: the sale of timber, bread, building materials, etc.

In the second half of the 19th century, Russia was an indispensable participant in world exhibitions, where textiles, brocade, engineering products, food products, jewelry, products of porcelain and glass factories, and handicrafts invariably received high awards.

Strengthening the commercial character Agriculture led to the rapid growth of the bread market, which more than doubled in 30 post-reform years. Of the total amount of sold bread, approximately 60% was consumed domestically, and 40% was exported abroad. The market for industrial goods, both for productive and personal consumption, developed even faster. A steady demand has formed in the country for machinery, agricultural implements, refined petroleum products and, above all, kerosene, fabrics, industrial-made shoes. Not only the urban but also the rural population became a major consumer.

In the second half of the 19th century, the volume of foreign trade turnover increased significantly, the country quickly entered the world market.

The total volume of export-import operations for 1861-1900 increased three times - from 430 million to 1300 million rubles, and the cost of exported goods exceeded the cost of imported goods by 20%. In the structure of exports at the end of the century, 47% was occupied by bread. During the post-reform years, the export of grain increased 5.5 times. At the end of the century, up to 500 million poods of grain were supplied to the foreign market annually. Other exported goods included flax, timber, furs, and sugar. In the same years, the export of crude oil and kerosene increased significantly.

The main import items were machinery, equipment for industry and agriculture. Metals accounted for a considerable share of imports, although Russia's own metallurgy was constantly developing. By the end of the century, purchases of raw cotton decreased due to the development of cotton-growing regions in Central Asia. Among the imported were tea, coffee, cocoa beans, spices. As before, the vast majority of foreign trade turnover - 75-80% - accounted for European countries - England, Germany, and the remaining 20-25% - for Asian countries and the United States.

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, a real “founder fever” flared up in Russia. In the same years, a similar process took place in almost all developed countries of Europe, in the USA and Japan, and was called "grunderism", i.e. mass founding of joint-stock companies, banks, insurance companies, followed by the issuance valuable papers, stock market speculation, etc.

The rapid development of industry and railway construction required large capitals that exceeded the capabilities of individual entrepreneurs, therefore, in the same years, the joint-stock business developed quite quickly. If before the reform in the country there were only 78 joint-stock companies with a total capital of 72 million rubles, then in the 1860-1870s 357 joint-stock companies with a capital of 1116 million rubles were created. True, many of these companies, which arose on the wave of stock exchange hype, turned out to be "inflated" and burst.

The process of concentration of large Russian capital, as in other countries, began mainly in the field of railway construction. Of all total investments, only 14% was invested in industry, while more than 60% was invested in railway transport, which played a significant role in the rapid growth of the industry.

A certain brake on the development of market relations was the underdevelopment of the credit system, the absence of commercial banks. The State Bank, established in 1860, issued mainly mortgage loans to large landowners secured by land, i.e. loans were almost not related to the production sector. "Founding fever" seized the banking business. In 1864-1873, about 40 joint-stock banks were established, among them: Private commercial Bank(1864) in St. Petersburg, Moscow merchant bank (1866). Moreover, from the very beginning they had a large share in the total resources of the country: already in 1875-1881, the five largest banks covered about half, and 12 banks - up to 75% of all banking resources in Russia. In those same years, the Volga-Kama Bank was the largest of them. The peculiarity of the credit system of this period was the presence of land credit banks, including the state Noble Land Bank (1885), which continued to divert cash loans from their productive use in the agricultural sector.

The formation of a market economy in Russia had its own specific features. Russia, like Germany, entered this path later than other European countries. was in the role of a catching up country, which allowed it to largely use their capital, their positive experience in science, technology, and in the organization of production.

In the 1880s, the first Russian associations of a monopolistic type appeared in industry and the first association of two St. Petersburg joint-stock banks - the International and Russian Bank for Foreign Trade (1881). However, the very first monopoly association in Russia arose not in industry, but in the insurance business: in 1875, eight insurance companies signed the Common Tariff Convention, after which they began to fight those companies that remained outside the convention in order to dictate their terms to them.

The first industrial association was founded in 1882, when five steel rail factories formed the Rail Manufacturers Union for a period of five years. This union had signs of the simplest syndicate and controlled almost all orders for the manufacture of rails for railways. It was followed by the unification of factories for the manufacture of fasteners for railroad rails (1884), for the construction of railway bridges (1887), for the production of various railway equipment (1889). This list of associations shows that railway construction was one of the most powerful and advanced branches of the national economy. Moreover, in this sector of the economy, almost all factories were new, there were few of them, which made it easier for entrepreneurs to collude about the quantity of products produced and the division of the market, about prices and terms of sale.

When creating the first associations in Russia, foreign capital played an important role. Thus, the basis of the cartel of iron-rolling, wire and nail works (1886) was German capital. In 1888, a cartel agreement was concluded on prices and the division of the market between the iron-rolling, wire and Putilov metal works. In the oil industry, a syndicate was formed with the participation of the enterprises of the Nobel brothers and the Rothschild company, and later, in 1897, both of these firms became parties to the international oil agreement.

The specificity of the emergence of the first corporation in the sugar industry (1887) was expressed in the fact that the majority of the united owners of sugar factories consisted of large landowners. Ten years later, the Sugar Refiners Society was created, which controlled almost all sugar production in the country and enjoyed the open support of the government. It included 206 out of 226 existing plants.

Agriculture continued to be a backward branch of the economy. The evolution of capitalist relations in agriculture proceeded very slowly.

After the reform of 1861, the situation of many landlord households worsened. Part of the landlords could not adapt to the new conditions and went bankrupt, the other ran the household in the old fashioned way. The government was concerned about this situation and began to take measures to support the landowners' farms. In 1885, the Noble Bank was established. He issued loans to landlords for a period of 11 to 66 years at the rate of 4.5% per annum.

The situation of a significant number of peasant farms worsened. Before the reform, the peasants were in the care of the landowner, after the reform they were left to their own devices. The bulk of the peasantry had neither money to purchase land nor agronomic knowledge to develop their farms. The debts of the peasants on redemption payments grew. The peasants went bankrupt, sold their land and left for the cities.

The government took measures to reduce the taxation of the peasantry. In 1881, redemption payments for land were lowered and arrears accumulated on redemption payments were forgiven for the peasants. In the same year, all temporarily liable peasants were transferred to compulsory redemption. In the countryside, the peasant community became the main problem for the government. It held back the development of capitalism in agriculture. The government had both supporters and opponents of the further preservation of the community. In 1893, a law was passed to suppress the permanent redistribution of land in the communities, as this led to an increase in tension in the countryside. In 1882, the Peasants' Bank was established. He provided the peasants with favorable conditions credits and loans for transactions with land.

Thanks to these and other measures, new features appeared in agriculture. In the 80s. the specialization of agriculture in individual regions has noticeably increased: farms in the Polish and Baltic provinces have switched to the production of industrial crops and milk production; the center of grain farming moved to the steppe regions of Ukraine, the South-East and the Lower Volga region; animal husbandry was developed in the Tula, Ryazan, Oryol and Nizhny Novgorod provinces.

Grain farming dominated the country. From 1861 to 1891 sown area increased by 25%. But agriculture developed mainly by extensive methods - by plowing new lands.

Natural disasters - drought, prolonged rains, frosts - continued to lead to dire consequences. So, due to the famine of 1891-1892. over 600 thousand people died.

LECTURE XLI

(Start)

Financial policy in the second half of the reign of Emperor Alexander III. - I. A. Vyshnegradsky and his system. – Extreme development of protectionism in customs policy and in railway tariff legislation. – The results of this system.

In my last lecture, I described the development of that reactionary policy which, in the second half of the reign of Emperor Alexander III, successively spread to all branches of government activity and made itself felt sharply in all areas of popular and social life.

The only easing of the reactionary course that we saw back in the mid-80s, as I already told you, was felt in the Ministry of Finance, where until January 1, 1887, if not an unconditional liberal, then, in any case, a humane , an honest and democratically minded person - N. H. Bunge. But at that time he was so persecuted by all sorts of intrigues and insinuations in court spheres and in the reactionary press that, being, moreover, already at an advanced age, he finally decided to leave the post of Minister of Finance and from January 1, 1887 was dismissed retired and replaced by a new minister, I. A. Vyshnegradsky. I. A. Vyshnegradsky was a man, undoubtedly, partly prepared for this position, but of a completely different type than Bunge. He was also a scientific professor, but not a theoretician-economist, but a scientific technologist and practitioner, undoubtedly very gifted, who showed his talents both in some inventions of a military-technical nature, and in very well-established academic courses, which he taught as a professor. students at the St. Petersburg Institute of Technology and at the Mikhailovskaya Artillery Academy. In particular, his contact with the military spheres through the artillery academy gave him an important advantage for the Minister of Finance: he managed to become well acquainted with the military economy and the military budget, which is such an important part of the general state budget in our country.

Thus, Vyshnegradsky appeared as Minister of Finance as a man, undoubtedly, to some extent prepared and informed - this cannot be denied to him. In addition, having early managed to make a certain fortune for himself thanks to his technical inventions, he then participated very successfully in various exchange speculations and exchange affairs, and this area, therefore, was also well known to him. But, at the same time, it is impossible not to admit that in his management of the Ministry of Finance, and especially in his financial and economic policy, Vyshnegradsky revealed a complete absence of any broad views and far-sightedness; for him, the most important and even the only, apparently, task was a visible improvement in Russian finances in the near future. In his financial policy, he set himself the same goal that Reitern once set himself, namely, the goal of restoring the exchange rate of the credit ruble, that is, the goal that, as you know, to a large extent, all finance ministers in Russia in the 19th century But not all of them pursued her with the same measures, and not all of them considered her their only task.

Be that as it may, the course of the Ministry of Finance with the replacement of Bunge by Vyshnegradsky changed quite dramatically. Under Vyshnegradsky, the main and immediate task of the ministry became the accumulation of large cash reserves in the cash departments of the state treasury and wide participation with the help of these reserves in foreign exchange transactions in order to put pressure on the foreign money market and in this way raise our exchange rate. At the same time, in customs policy, the Russian government began to move with new energy along the path of protectionism, which reached its climax under Vyshnegradsky. In 1891 a new customs tariff was issued, in which this system was taken to an extreme. At the same time, considering the strengthening of the Russian manufacturing industry to be a very important matter for the success of its measures, the Ministry of Finance begins to listen with extreme attention to all complaints and wishes of representatives of large-scale factory industry and undertakes, on their initiative, to revise what is, in fact, still very little developed factory industry. legislation that was worked out in the interests of the workers under Bunga. Under Vyshnegradsky, the rights of factory inspectors established under Bunga are extremely diminished not so much by new legislative norms as by means of circular explanations, which very soon affect the composition of the factory inspectorate, because under these conditions the most devoted and independent representatives of this inspectorate, seeing the complete impossibility of acting in accordance with their conscience, and even in accordance with the exact meaning of the law, retire. Thus the institution of factory inspection is greatly changed for the worse. Russian large-scale industry, thanks to a number of protective measures - and in particular the careful attitude of the Ministry of Finance to the question of the direction of railway lines beneficial for the domestic manufacturing industry and of such railway tariffs that would strictly correspond to the interests of large-scale industry, especially the central, Moscow region, is becoming in this time in especially favorable conditions. It can be said that these favorable conditions are artificially created for it; it becomes a favorite brainchild of the Ministry of Finance, often contrary to the interests of other segments of the population and especially contrary to the interests of all agriculture, the state of which was especially unfavorably affected by the protective customs tariff of 1891, which extremely increased the price of such important items in agricultural life as, for example, iron and Agreecultural machines. Agreecultural equipment.

Meanwhile, at this time, we not only do not see an improvement in the condition of the masses of the people, despite all the palliative measures taken under Bunga, but, on the contrary, we observe the continuing ruin of the peasantry, which I described to you in one of my previous lectures. In the end, however, this undermines the conditions for the internal sale of products of the manufacturing industry, which satisfies the needs of the broad masses of the people, for example, the conditions for the sale of products of the paper-weaving industry. The impoverished domestic market soon becomes cramped for her. To some extent, compensation for it is the external market in the east, acquired by the conquests in Central Asia, but it soon turns out that this is not enough, and now we see that towards the end of the reign of Emperor Alexander III, a new idea is gradually being created - to promote the sale of our products. industries as far east as possible. In connection with this is the idea of building the Siberian railway - an idea that is being developed very widely; is the question of access to the Eastern Sea, of acquiring an ice-free port in the Far East, and in the end, all this policy, already before our eyes, leads to the emergence and development of those enterprises in the Far East, which are already in the ministry of S. Yu. Witte in at the very beginning of the 20th century. led to the Japanese war and the collapse that followed.

To end financial and economic relations during the period under review, I will say a few more words about the expansion of our railway network, which has played an extremely important role here. By the end of the reign of Alexander II, the railway network did not exceed 22.5 thousand versts, and during the thirteen-year period of the reign of Alexander III it had already developed to 36,662 versts, of which 34,600 were broad-gauge. In the matter of building railroads, the old policy of Reitern was supported in the sense that these railroads, as before, were directed in such a way as to, on the one hand, facilitate the transport of raw materials to the ports and thus, precisely by increasing exports, create a favorable moment for our balance of trade and for improving exchange rate, and on the other hand, as I mentioned, the ministry sought, by establishing differential railway tariffs, to create the most favorable conditions for the transportation of products of the factory industry of the central provinces. To this end, even a special institution was created within the Ministry of Finance - the Tariff Department, headed by S. Yu. in a wider arena, in solving the common political problems of our time.

Another feature of the new railway policy, a feature opposite to Reitern's policy, was the construction of roads by the treasury and the redemption of the old private railway lines into the treasury. During the reign of Emperor Alexander III, the length of state-owned railways increased by 22,000 versts, while the length of private roads, despite the construction of new private lines, decreased by 7,600 versts due to the redemption of old lines to the treasury.

These are the general features of the financial policy, which undoubtedly prepared and deepened a new aggravation of Russian socio-economic conditions at the beginning of the 20th century. These conditions developed hand in hand with the crisis that the Russian population had to endure after the crop failure of 1891-1892, which caused extreme poverty and even famine in as many as twenty, mostly black earth, provinces. This crisis was, so to speak, the final touch in the general picture of Russia that we see at the end of the reign of Emperor Alexander III, and at the same time was a powerful factor in those changes in subsequent years that will, perhaps someday, form the subject of the next part of my course on the final period of the history of Russia in the 19th century.

It was aimed at solving two most important tasks: accelerating the economic development of the country and supporting and strengthening the positions of the nobility. In solving the first task, the head of the Ministry of Finance N.Kh. Bunge was guided by the expansion of the domestic market, the simultaneous rise of agriculture and industry, and the strengthening of the position of the middle strata of the population.

On May 9, 1881, a law was passed to reduce the size of redemption payments and write off arrears on them for previous years. The losses incurred as a result of the treasury were called upon to be covered by an increase in land tax by 1.5 times, a tax on urban real estate, as well as excise rates on tobacco, alcohol and sugar.

The gradual abolition of the poll tax (1882-1886) was accompanied by development other forms of taxation: income from cash deposits increased, excises increased, commercial and industrial taxation was transformed, customs duties were significantly increased (almost doubled).

Burdensome for the country's budget was the system of state guarantees of income for private railways. Under N.Kh. Bunge introduced control over the railway sector and the state began to buy private and finance the construction of state-owned railways.

In 1883, the creation of joint-stock private banks resumed. In 1885, the Noble Land Bank was created, designed to support landownership (N.Kh. Bunte objected to its creation).

In January 1887, under pressure from conservatives who accused him of being unable to overcome the state budget deficit, Bunge resigned.

I.V., who replaced him. Vyshnegradsky (1887-1892), a well-known mathematician and a major stock exchange dealer, retained the general direction of the economic and financial policy of his predecessor, but focused on the accumulation of funds and the appreciation of the ruble through financial and exchange transactions. Vyshnegradsky increased protectionism in customs policy.

In general, for 1880-1890. the increase in import duties brought about an increase in revenue of almost 50%. In 1891, a general revision of the customs tariff was carried out with the aim of its centralization and the elimination of local tariffs. Thanks to the protectionist customs policy, imports to Russia foreign capitals. In the late 1980s, the state budget deficit was overcome.

industrial development Russia

in the 80s - early 90s.

In most major industries Russia by the 80s of the XIX century. completed the industrial revolution. Economic politics finance ministers Bunge and Vyshnegradsky contributed to the accelerated development of industrial production.

Russia

ranked first in the world in terms of growth in oil and coal production.

The 1990s were marked by active construction of industrial enterprises.

Despite the rapid growth Russian industry, its lagging behind the developed countries of the West (USA, England, Germany, etc.) both in terms of technical equipment and power supply, and in terms of coal, oil production, metal and machinery production per capita remained very significant.

Total production of heavy industry Russia by 1896 was less than 1/4 of all manufactured products. The leading place in the economy was retained by the light industry. Only textile production gave products 1.5 times more than the extraction of coal, oil, minerals, metalworking and metallurgical industry combined.

Since 1881 in Russia the industrial crisis began. The consequences of the Russian-Turkish war of 1877-1878, the fall in world grain prices, as well as the general slowdown in the development of the domestic market due to a sharp decrease in the purchasing power of the peasantry, had a particularly acute effect on the economy. In 1883-1887. the crisis gave way to a long depression, but at the end of 1887 there was a revival, first in heavy and then in light industry.

Transport.

The government paid great attention to the development of railway transport, which was given not only economic, but also strategic importance. Since the 1980s, the construction of new railways and the redemption of private railways to the treasury began. By the mid-90s, 60% of the entire railway network was in the hands of the state. The total length of the state railways in 1894 amounted to 18,776 versts; in total, by 1896, 34,088 versts had been built. In the 80s, a network of railway lines was developed along the western borders Russia.

Developed river and sea shipping. By 1895, the number of river steamships was 2,539, an increase of more than 6 times compared to the pre-reform 1860 year.

The development of domestic and foreign trade was directly related to the development of transport. The number of shops, shops, commodity exchanges (especially near railway stations) is increasing. Domestic trade in Russia(without petty trade) in 1895 amounted to 8.2 billion rubles, an increase of 3.5 times compared to 1873.

The external market developed rapidly. In the early 1990s, exports exceeded imports by 150-230 million rubles. annually. The active foreign trade balance was achieved mainly due to the protectionist tariff policy of the state. In the 1880s, import duties on coal were raised three times, in 1885 duties on imports of iron were raised, and in 1887 on imports of cast iron. In the second half of the 1980s, between Germany and Russia the customs war began: to restrict the import of agricultural products into Germany Russia

responded by raising import rates on German manufactured products.

The first place in export was firmly occupied by bread.

In second place, displacing wool, came the forest.

The export of industrial goods grew rapidly, reaching 25% of all exports. In the mid-1990s, cars took the first place in imports, and the import of raw cotton was in second place. Then came metal, coal, tea, oil.

Main foreign trade partner Russia was Germany (25% Russian exports, 32% imports). England moved into second place (20% of exports and 20% of imports). Third place in Russian exports were occupied by Holland (11%), in imports - by the USA (9%).