Let me remind you that the presented goods (not all, but many) could not be bought on free sale. And, what was in the capital's stores was much more expensive than in this catalog. In it, the prices are cunningly indicated in rubles, but we are talking about checks of a mail order or foreign currency rubles. The point was that our specialists working abroad were paid not in foreign currency, but in these same rubles. And they could buy them in our stores, exchanging them for such a buzz, as in this catalog. Or buy jeans, a radio tape recorder, cassettes ...

Pasta in such boxes I remember. Not a big deficit. But there were no Italians. I'm surprised they're about the same price...

The same can be said about coffee. The price was determined not by the market, not by demand. Same weight - get the same price. Naturally, the imported one was much more scarce. However, ours was not in the province either, they were brought from Moscow.

Of interest is the offer of alcoholic beverages. These dry Georgian wines were in stores and were not in demand. Sometimes they were taken, if suddenly there were no fortified ones. They drank, grimaced, called sour meat and compote.

Portuguese and Spanish wines are good. And even more so for this price. And pay attention to the price of Soviet Champagne. Of course, it is unreasonably overpriced. But, this was the reason for the myth of excellent quality and terrible demand abroad for this product. That is, they raised the price for foreigners, and, say, sailors, having bought in a regular store, this product was changed for any consumer goods. In addition to champagne, this group included watches, cameras ...

Cinzano and Martini were offered at the same price. And this price for 83 years old was 3 rubles. Special) At the same time, we often drank the same vermouth, buying it in "Torgmortrans" stores. And it was a lower class vermouth. Hungarian "Kecskemet", "Carmen", Bulgarian "Marka". And they all cost 4 rubles per liter bottle.

Imported canned beer at one price, according to the wonderful Soviet tradition))

Ah, what wonderful bottles ... Exactly, before the grass was greener)

And this is the holy of holies - sausage. From this, a Soviet person could have a nervous breakdown)

At the same time, according to today's ideas, the assortment is rather meager. But then it seemed that it was just an unheard-of abundance ...

Black caviar is five times more expensive than red

Now it seems to be normal. Today, black is about 20 times more expensive ... But then, it seemed wild. At that time, we easily bought black caviar from bracos, I don’t remember the price, but it’s quite affordable. Red, on the contrary, was something exquisite, not very accessible)

The real poverty of the assortment is clearly visible in the choice of cheeses. Soviet, Dutch, Swiss ... Yes, they were not bad, and even more so. But how can this be compared with any modern supermarket? "Friendship", "Amber"...))

And back to alcohol. Armenian cognac three stars for 2.50! Ah, if only! We took him 10 each, if we were lucky. They sorted it out quickly.

I'm not talking about the prices for France. Well done, write as it sounds - Ennessy. Now they would write Hennessy)

But Camus Napoleon stood in Moscow stores for 50 rubles per bottle. An exorbitant price for a Soviet person. Quite another matter - 17 rubles)

In 1983 we bought Russian vodka at 5-30 for a bottle with a peakless cap, and at 5-50 with a screw. For diplomats, the same one cost 1-43 ...

Very interesting prices for cigarettes. In 1983, Marlboro, Camel, and Winston began to appear in our stores ... All of them cost a ruble per pack, and a little later at 1-50.

Today the market has divided all these brands into different price groups. Curious pricing in foreign trade. All imported cigarettes of standard length cost 40 kopecks. per pack, and 100 mm - 45 each))

Well, and finally, so that the workers would not have illusions, Vneshposyltorg explains that the goods presented are not intended for them, the mob, but for foreign diplomats

More interesting pages from the catalog...

In a country with an artificially high purchasing power of the national currency, as well as complete price control at the state level, the ingress of any foreign currency threatened to disrupt the established order. Article 88 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR forbade having or carrying out any transactions with any money other than Soviet rubles. Even collecting "foreign" banknotes was considered illegal.

All-Union Association "Torgsin"

In 1931, the All-Union Association for Trade with Foreigners was created, which received the abbreviation "TORG S IN" (that is, trade with foreigners). This organization existed for 5 years and was engaged in the sale of goods for foreign currency (only for foreign citizens), as well as for pre-revolutionary gold coins, jewelry, jewelry, antiques, etc. In exchange, special warrants were issued with a specified denomination, for which various scarce goods, including imported goods, could be obtained in special stores.After the closure of Torgsin in 1936, the issuance of goods on account of wages to foreign workers was carried out using a cashless system. To do this, it was necessary to select a product from the catalog and after a while receive it in special departments. One of these departments was on the third floor of GUM in Moscow.

The system had limited functions and did not allow to fully serve citizens who worked abroad. For example, they could give out clothes in only one size.

Certificates and checks of Vneshposyltorg

In the 1960s, the USSR actively developed international cooperation, especially with the countries of the socialist camp. Thousands of workers go abroad and are paid in local currency. Upon arrival, all Soviet citizens are required to exchange the remaining money for special Vneshposyltorg certificates. This organization was managed by the USSR Bank for Foreign Trade (Vneshtorgbank), which carried out any international settlements and control of foreign exchange transactions. The certificates had the denomination indicated on them (from 1 kopeck to 250 rubles). Foreigners could import currency to a limited extent without exchanging it for certificates.Certificate 1966 series D (for diplomatic workers)

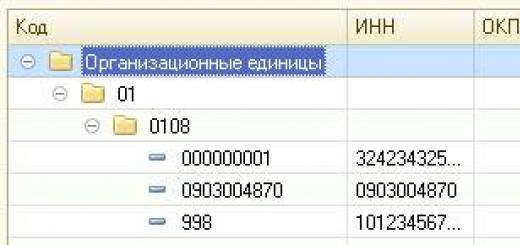

It was possible to purchase goods for certificates in Beryozka stores, which were available in large cities of the RSFSR, as well as in some settlements with a large flow of foreigners (Vyborg, Yalta, Sevastopol). In other republics of the USSR there were other names: Chinar in Azerbaijan, Chestnut in Ukraine, Dzintars (Amber) in Latvia. For foreigners who had currency, there were other shops with the same names, but closed to everyone else. In such closed stores, certificates could also be accepted, but only Vnesheconombank's "D" series, which were issued to diplomatic workers.

Vneshposyltorg certificates were of three types:

with blue stripe for workers in socialist countries (such as Cuba, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Mongolia, Romania, Hungary, East Germany, Poland and others);

no stripe for workers in capitalist countries (USA, Germany, England and others);

with yellow stripe for workers in Third World countries, that is, whose money was not widely convertible (countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America).

The stripes were applied diagonally over the certificate. Otherwise, they were completely similar to each other. In Beryozki, the cost of goods was expressed in rubles, checks with a blue stripe were accepted at face value, and checks with a yellow stripe and without a stripe at a rate of 1:4.6. The difference in coefficients was necessary to equalize the purchasing power of wages. In the socialist countries, the ratio of wages and prices was approximately the same, while in the West it was about 4.6 times higher.

In addition to food, some expensive goods, such as cars, were also sold, and coefficients also applied to them. For example, "Volga" cost 5500 rubles, and for holders of certificates with a yellow stripe or without it at all, only 1200.

There was an unofficial exchange rate for certificates for Soviet rubles. This procedure was subject to a prison sentence, but such cases were still widespread. For example, for a certificate with a blue stripe they gave 1.5-2 rubles, with a yellow stripe - 6-7 rubles, and those without stripes were valued the most - 8-9 rubles. Certificates gave the right to buy scarce goods. Beryozka stores were overflowing with assortment compared to the empty shelves of ordinary stores.

Since 1974, instead of all types of certificates, checks have been introduced, with which wages were accrued immediately according to the established coefficient. They were of the same sample, denomination from 1 kopeck to 500 rubles. The main reason for the cancellation of certificates was the numerous speculations during their exchange.

1976 check for 25 kopecks

Certificates, and then checks were issued, including foreign money transfers. Another of their applications was participation in housing cooperatives, where both certificates and checks were accepted at the rate of 1:1 to the Soviet ruble, for example, on account of the payment for the construction of a garage.

As already mentioned above, the range of goods in Beryozki was much larger than in ordinary stores. Here is a list of some products and prices taken from the price list of one of the Moscow stores:

chocolate "Alenka" - 16 kopecks;

chocolate medals (7.5 g) - 3 kopecks;

sweets "Squirrel" (1 kg) - 1 r 50 kopecks;

a box of sweets "Bird's milk" (320 g) - 56 kopecks;

bagged mushroom soup "Knorr" - 21 kopecks;

instant coffee (50 g) - 60 kopecks;

granulated sugar (500 g) - 20 kopecks;

buckwheat (1 kg) - 39 kopecks;

cheese "Friendship" (30 g) - 3 kopecks;

sausage cheese (1 kg) - 89 kopecks;

sausage "Soviet" raw smoked (1 kg) - 3 r 25 kopecks;

sausages "Russian" (1 kg) - 1 r 10 kopecks;

hazel grouse (game, 1 pc.) - 91 kopecks;

sprats in oil - 45 kopecks;

Atlantic herring (can, 5 kg) - 3 r 11 kopecks;

milk (0.5 l) - 12 kopecks;

halva (250 g) - 19 kopecks;

Dutch milk chocolate (225 g) - 1 r 40 kopecks;

cake "Fairy Tale" - 78 kopecks;

chewing gum (Denmark, 5 plates) - 15 kopecks;

pineapple (1 kg) - 76 kopecks;

apple juice (Bulgaria, 1 bottle) - 26 kopecks;

white Georgian wine (1 bottle) - 1 r 24 kopecks;

champagne "Soviet" (1 bot.) - 2 r 57 kopecks;

"Martini Bianco" (1 bot.) - 1 r 15 kopecks;

vodka "Stolichnaya" (1 bottle) - 1 r 3 kopecks;

Cigarettes "Marlboro" - 24 kopecks.

1976 check for 20 rubles

The end of the era of "Birches"

In January 1988, the issuance of goods for checks was discontinued, their owners formed huge queues at Beryozki in the last days of the system's operation. For another 4 years, cashless payments were carried out, and then the chain of stores was privatized, and trade began to be carried out only for foreign currency. In the mid-90s, the stores were closed due to the appearance of numerous supermarkets with an abundance of goods that Beryozki could no longer compete with. Some of them have been preserved in individual cities, but now they are ordinary stores with a standard assortment.Other types of currency substitutes

In the 60-80s, the Torgmortrans organization distributed goods among long-distance sailors. For this purpose, there were Albatros stores in port cities, and sailors received special cut-off checks of the A series, the denomination of which was expressed in rubles and kopecks. This system lasted until 1992.Cut-off checks of the D series had a similar design with the checks of the A series and were used to pay travel allowances to representatives of Soviet foreign diplomatic missions. Checks were filed into checkbooks for a certain amount and issued upon arrival in the USSR. In large cities, they could be exchanged for goods in special departments of Beryozka stores. Holders of diplomatic checks had privileges when buying a car. Resale of checks was considered a crime, but such cases were not uncommon.

In addition to the above, in the 50-80s there were special "cruise checks" issued to Soviet citizens when making international cruises, flying or traveling by rail. For these checks it was possible to purchase goods on the way, unspent checks could be exchanged again for rubles.

Cut-off check of 1989 for 1 ruble of series A (for sailors)

Traveler's checks were sometimes used for business trips and could be exchanged upon arrival. They ruled out the possibility of theft, since they had the signature of the owner, and the issuance was carried out only after the owner signed for the second time. Checks could have a denomination not only in rubles, but also in foreign currency if they were issued to foreign citizens.

Photos provided by site users: Slim, SAKHAR, Andrey78, Tayna.ya.

It is well known what a heavy burden on the Soviet economy in 1979-89 was the cost associated with the participation of a "limited contingent".

In addition to official spending on Afghanistan in one form or another, the unofficial Afghan and near-Afghan economic system formed as a result of the stay of the Soviet military contingent in a foreign country.

Here we must recall the flow of goods that poured into the Union from the south. Most of them came to Soviet consumers in the suitcases of officers, soldiers and civilian specialists returning from an undeclared war, or in secluded places of the withdrawn equipment. In turn, Soviet goods that were in short supply there were sent to Afghanistan in large quantities quite unofficially.

And where there is international trade, its own currency system inevitably arises. The published memoirs of veterans of the undeclared war in Afghanistan allow us to get a certain idea about it.

Perhaps, Aleskender Ramazanov covered the “monetary” side of the Afghan war in most detail: “ Cash allowance soldiers and sergeants in Afghanistan was beggarly and fluctuated between 20-40 rubles a month. Part of this amount was exchanged for VPT (Vneshposyltorg) checks. Despite the ominous warnings, the check had nothing to do with currency. This surrogate for the ruble could be used to pay in Voentorg stores in the 40th Army or, until the beginning of 1989, on the territory of the USSR in the "currency" shops "Beryozka".

In an incomprehensible way, when exchanging the due amount, a serviceman was given two and a half checks for a ruble, and when spending accountable check amounts, officers were charged four rubles for a check ruble - as if in a library when a book was lost ...

The essence was clarified by the “black market” in the Soviet Union, where a VPT check cost about three and a half rubles (close to the real exchange rate of the US dollar, contrary to the legend about the “buck” for sixty Soviet kopecks).

Officers and warrant officers, depending on the rank, position, time of service in the DRA, received a double salary for their position, from which from 45 to 150 rubles were deducted and exchanged for checks of the VPT. Accrual occurred daily, strictly in accordance with the number of days spent abroad. In 1981, junior officers received about 180 checks for a full month in the DRA, senior officers - 250. By the end of the Afghan campaign, this type of payment had almost doubled. Numbered stamps were put on banknotes of 100 and 50 checks, according to them it was possible, in theory, to trace where he came from to the “Afghans” or to the “non-Afghans” in the Union: in Beryozki they demanded identity cards, passports, military tickets from buyers - sometimes at the entrance to the store, not to mention the checkout. Didn't help! In the fight against smugglers and speculators, wide red stripes-lampas and formidable inscriptions about a special purpose for military trade appeared on checks. The wonderful properties of checks include the following: if an officer could pay a quarter of the cost of the Volga with checks, then he was allowed to purchase a car out of turn.

The "Afghans" loved the checks of the VPT, since it was easier to import them into the USSR and it was safer to pay off the plunderers of military property and socialist property. An excess of afghani (Afghan currency) could arouse suspicion in a soldier, and checks could be familiar. Accumulated! Friends have dropped!

And yet - the check was assigned and canceled! In January 1989, to complete the withdrawal of troops, Beryozka stores closed and the check could be exchanged for Soviet rubles one for one with army treasurers. Here is such a currency substitute!

And since Afghan shopkeepers bought everything they could sell from Soviet soldiers and officers, they needed a lot of checks. Imagine their reaction to the cancellation of checks!

“Normal people don’t do that,” dukandor Ali-Muhammadi from Mazar-i-Sharif assured the author of these lines. The Shah is gone. Daoud is gone - paisa lives. Taraki, Babrak - all Afghanis walk! What is your country? Canceled the money, right? A panel of red-striped checks of the VPT adorned the northern wall of his dukan. However, the Afghans already had a lesson in 1917. Their chests are probably glued with royal banknotes to this day. So we haven't learned...

As for the prices for consumer goods in military stores - "chekushki", they roughly corresponded to the all-Union. In the "chekushkas" they immediately organized: "deficiency", the issuance of goods with the permission of the unit commander, the restriction of "sales in one hand", the ban on the sale of certain goods to soldiers and sergeants, and a complete "bummer" to advisers! Those sometimes were not allowed into the territory of the units.

Showcases and shelves of "chekushkas" were packed with fruit juice surrogates from Yugoslavia, dry biscuits, hard candies, Chinese canned meats. Under the "record" were sold tracksuits, suitcases, "diplomats", tape recorders from Japan and Germany. Zi-zi lemonade was considered luxury, which, however, was called "sisi", with an emphasis on the first syllable, of course. By the time the troops were withdrawn, when a considerable check mass had accumulated in the hands of the servicemen, the “chekushkas” were mysteriously empty.

Check notes were 100, 50, 10, 5, 1 ruble and 50, 10, 1 kopeck. A penny could buy a box of matches or an unstamped envelope. After being accepted at the store, the checks were canceled (the triangle was cut around the edge).

During all the years of the Afghan campaign, there was a categorical prohibition on the purchase of goods in local shops (dukans), and therefore, everything that was not purchased in “chekushkas” could be seized on “legal grounds”. This concerned less officers, and a soldier could be cleaned naked before being sent home - in a unit, at a transit point or at customs. Which happened all the time and everywhere. Shmon is an immortal thing!

But it was a wise political and ideological decision: how can something sensible be brought from an undeveloped country, which we undertook to help everyone, down to flesh and blood? The money theme was rather dry and stingy deposited in the memory of veterans. Far from a decisive factor for the Soviet soldier of those times.

It is not entirely clear why the author dates the closure of Beryozki to January 1989? January 1988 is usually mentioned, not 1989. In the first days of January 1988, the Government of the USSR announced the liquidation of the system of trading for checks, in the course of the campaign "to fight against privileges" and "for social justice." At the same time, huge queues arose - the owners of the checks tried by any means to get rid of them before the announced closing date.

But one cannot but agree with the fact that the financial factor was not decisive for the Soviet soldiers and officers of those times. But their readiness to serve their country and fight where ordered was too shamelessly exploited in incredibly difficult conditions.

Magic officer's hat

Here is a description of how the first practical lesson in Afghan currency studies was received by officers who recently arrived in Afghanistan, made by helicopter flight engineer Igor Frolov:

“When drowsiness began to fall on the silenced flight technicians, two Afghan soldiers from the airfield guard approached the board. Sticking their heads in the door, they examined the interior, looking under the benches.

– Jam, sweets, liver? the tall one asked.

“Nothing, they haven’t earned it yet,” Lieutenant Molotilkin spread his hands.

- This! - one soldier pointed to the winter hat of the flight engineer F., lying on an additional tank.

What about the keys to the apartment? - said the flight engineer F.

Suddenly, a black-haired captain of the Soviet army appeared behind the Afghan army soldier. The flight technicians did not hear how the Toyota drove up - she dropped off the passengers at the KDP so that the two majors got acquainted with the chief of the airfield, Colonel Sattar, and the captain went to the sides.

- What, are you afraid to sell your honor? - he asked Lieutenant F. - So honor, she is in a cockade, but there is no cockade anymore. A man, not to mention a military officer, must have money ...

The first days, until they were uniformed, the flight engineer F. went around in his gray-blue officer's cap, taking off his golden cockade - there should not be unmasking details shining in the sun on the field uniform.

- Fuck noise, dust? the captain asked the soldier.

- Hub! - said the soldier, smiling white-toothed at the Russian giant.

The captain went up to the cabin, took the hat of flight engineer F., showed it to the soldier:

– Du hazor?

“No, no,” the soldier shook his head. - Hazor...

What about winter in the mountains? the captain said. - Your dushman brothers are cold, however ...

- Dushman is the enemy! - Smiling, said the soldier.

- All right, brother of the enemy, - said Rosenquit, - like hazor panch sad! and he thrust his cap into the soldier's hands.

He immediately put it on his head, took out a thin bundle from his bosom, peeled off several bills and gave it to the captain.

The captain opened a bag of orange percale, in which, judging by the protruding edges, packs of Afghans were packed, put the soldier’s money in it, took out a banknote of fifty checks of Vneshposyltorg from his pocket and handed it to flight engineer F.

- What is it? - the flight engineer F., amazed at the speed of selling his cap, asked.

“This is the first lesson of the free market and illegal foreign exchange transactions,” the captain said. - A hat worth eleven rubles in the Voentorg, besides heavily used, was sold for one and a half thousand afoshkas to a friendly Afghan soldier, for whom a warm thing in winter is more necessary than Montana jeans, which you can buy in a local dukan for the same one and a half thousand. So that you understand your gain, I gave it to you in checks, at the rate of one to thirty. In the Union, these half a hundred checks will be exchanged for you near Beryozka one to three for 150 rubles, that is, your profit will be more than a thousand percent ...

- Some kind of nonsense ... - the flight engineer Molotilkin said admiringly. - It turns out that if I bring a hundred of these hats here, you can buy a Volga in the Union?

- "Volga" can be bought by correctly scrolling a case of vodka, - the captain laughed. – But this is a question of import-export, then you will understand. By the way, for these half a hundred checks you can buy a bottle of vodka here, and at the Tashkent airport you need to put so much in your passport at the cash desk so that you can then sell a ticket home for rubles. Such are the paradoxes.

Flight engineer F. was struck by this simple but powerful mathematics of the market. True, he was embarrassed that he so unprincipledly allowed to give into the wrong hands his native hat, doused with jelly in the dining room, scorched by the stove of the squadron house at the Amur airfield, kerosene, which had served him as a pillow so many times ... He suddenly felt that he had sold his smaller sister, and he felt ashamed. And even scary - I remembered my grandmother's remarks - "do not wave your hat - your head will hurt" or "do not throw your hat anywhere - you will forget your head." Is this not a sign that he will leave his stupid and greedy head here?

To distract himself, he began to think about how, upon returning to the base, he would go to the “chekushka”, where the saleswoman Luda, nicknamed Globus, would sell him a block of Java cigarettes, a bottle of Donna cherry, a pack of cookies, a box of chocolates and, probably, a can of crabs . And then he will go to a bookstore and buy a black two-volume Lorca there, so that, closing after dinner on board, he will read, lying on a bench, about the moon over Cordoba, smoking, shaking the ashes into the open porthole and drinking Donna ... "

Before the eyes of flight engineer F., a winter hat worth 11 rubles in the military department, heavily second-hand (that is, used), doused with jelly and pro-kerosene, turned into 50 precious checks. As the old-time captain quite rightly noted, a warm thing in winter is more necessary than Montana jeans. Who in the then Soviet Union would understand this? An unfortunate tattered hat - and a precious Montana. How many dramatic stories due to the lack of this most coveted "Montana" from a guy or girl happened at that time ... And then a hat as the equivalent of "Montana". Monetary Afghan fiction, incomprehensible to ordinary citizens of the USSR.

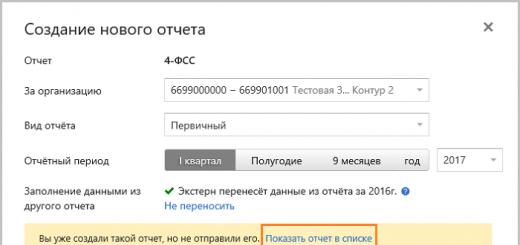

). Vneshtorgbank's checks paid salaries to Soviet citizens who worked abroad: mainly specialists working under construction contracts of the USSR, as well as specialists (for example, teachers, doctors and military advisers) working under contracts with foreign public and private institutions (hospitals, universities, etc.) .), as well as sailors, ordinary employees of embassies and other persons within the USSR who received fees or transfers in foreign currency.

The main purpose of the introduction of certificates, and later VTB checks, was the desire of the Soviet state to limit foreign exchange spending on the salaries of citizens who worked abroad (especially in capitalist countries, where otherwise employees would withdraw their salary in foreign currency and spend it all on the spot), as well as reduce the flow of private clothing imports into the country from uncontrolled sources. During their stay abroad, part of the salary of foreign workers in foreign currency was voluntarily (but not more than 60%) * transferred to an account with Vnesheconombank, from which it was possible on the spot (usually through an adviser on economic issues at the Embassy of the USSR) or upon returning to the USSR to receive a pre-ordered amount in the form of certificates (later - checks). Some categories of foreign workers of foreign trade organizations and diplomats could also bring into the USSR a limited amount of foreign currency, which they were required to convert into certificates (checks) no later than the deadline, otherwise their possession of currency was also considered illegal.

Certificates (bons for sailors) appeared in 1964. Previously, on the third floor of GUM and in the Central Department Store there was a system of so-called. “closed special departments”, where foreign workers or their relatives were given things ordered in advance from catalogs. The system was extremely cumbersome and practically did not allow the sale of small consumer goods (for example, it was impossible to exchange shoes for the right size). As a result, a more flexible system of Vnesheconombank's certificates was introduced. There were three types of them: "certificates with a blue stripe" - paid to citizens who worked in the CMEA countries (the coefficient of crediting to the account was 1: 1); “certificates with a yellow stripe” - were paid to foreign workers who worked in countries with non-convertible currencies, that is, in the third world, for example, India, African countries, etc. (ratio 4.6:1) and "bandless certificates" - paid to those working in countries with SLE (ratio 4.6:1). thus, the “yellow-striped” and “striped” certificates were behind the scenes a physical analogue of the notionally countable foreign currency “golden” ruble, performing the quasi-function of “Soviet chervonets”, but, unlike their predecessors, they did not have official circulation in wide circulation and were not in the hands of persons who did not able to document the legal source of origin, were equated with foreign currency, the possession of which was criminally punishable for Soviet citizens (Article 88 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR).

Certificates and bonds (later checks) could be legally purchased exclusively in the network of special stores - "Birches", in addition, they could be made as a contribution to the housing cooperative, but only at a ratio of 1: 1 to the usual ruble, which was also an additional article state income. The essence of the system of certificates was that foreign workers in different countries, with formally comparable salaries (close to the average for the Union), actually received salaries that differed significantly in terms of purchasing power. For example, the salary of a Soviet translator in India, which was conditionally 200 rubles, was actually 920 rubles in “yellow stripe certificates”, and the salary of a translator, for example, in Hungary, was 400 rubles. in "blue-stripe certificates" was the same 400 rubles. Accordingly, in "Beryozka" for blue and yellow striped certificates they sold only clothes, carpets, crystal and other consumer goods produced by the CMEA, but also cars. And for “bandless certificates”, high-quality imported consumer goods were also sold, including Western audio equipment and scarce food products. Especially evident was the difference in the purchasing power of certificates on the example of cars, so the Volga GAZ-21 cost 5.5 thousand rubles. in the "blue stripes" and only 1.2 thousand in the "unstriped" and "yellow stripes"; "Moskvich-408", respectively, 4.5 thousand and about 1.0 thousand, and "Zaporozhets" - 3.5 thousand and 700 rubles. Such a clear inequality led to the accumulation of discontent among ordinary foreign workers and created a field for "speculative operations", that is, the exchange of certificates of various types "between friends", as well as the "black market", which operated despite a strict ban on such operations (up to 8 years according to article 88 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR), where the rate of certificates to the Soviet ruble in the early 70s was 1: 1.5-2 for "blue-striped", 1: 6-7 for "yellow-striped" and 1: 8-9 for "striped ". By the way, for senior diplomatic workers (from the level of an adviser and above) there were separate certificates of type “D”, which were accepted for payment on an equal basis with cash from foreigners in a parallel system of currency shops - “Birches”.

Thus, in the USSR there were two completely separate (check and currency) trading systems of stores (in the RSFSR - "Birch", in the Ukrainian SSR - "Kashtan", and in the Latvian SSR - "Dzintars"). Only foreigners, diplomats and the highest party nomenklatura could legally shop in currency shops. Ordinary foreign workers were supposed to use only check "Birches", in turn, closed to other Soviet citizens who had only Soviet rubles.

Most ordinary Soviet foreign workers regularly transferred a significant part of their salaries abroad to the accounts of Vnesheconombank, which was facilitated by strict customs restrictions on the importation of durable goods into the USSR by individuals, as well as the sale of such prestigious and scarce goods as Volga cars exclusively for checks. With a significant expansion in the 70s of the number of citizens traveling abroad to work and to simplify the operation of the Beryozka system, in 1974 certificates of all types were replaced by "Vneshtorgbank checks" of a single sample.

When receiving money transfers from abroad, they necessarily passed through Vneshtorgbank and within the USSR were also issued by checks, and not in the original currency.

Officially, checks for ordinary Soviet rubles were not exchanged (they could only be counted at the rate of 1:1 with contributions for housing cooperatives or a garage), and the black market rate ranged from 1:1.5-2 (in the late 70s) to 1:10 ( in the second half of the 80s), which, however, did not prevent this type of “shadow business” in Moscow and Leningrad from expanding to a mass socio-economic phenomenon by the mid-80s, and also brought to life a new criminal specialty, “cheque breakers”, that is, swindlers who deceived foreign workers during the exchange by handing them "dolls" instead of ruble cash. Since foreign workers and persons equated to them committed a criminal act, there were usually no complaints about scammers to the police, and besides, many “comrades” assigned to “Birches” to keep order were themselves already in the share of the breakers.

These negative phenomena became known to the general public in the era of glasnost, causing a massive "wave of indignation", not so much with the fact of the existence of "Birches", but with the difference in the actual amount of wages of "simple drillers in the Karakum and Sahara". As a result, the system of trading for cash checks in Beryozka stores was recognized by the leadership of the USSR as socially unfair and liquidated in 1988 in order to divert public attention from the nomenklatura "special distributors" and mask the general deterioration in the state of Soviet trade after the introduction of the "dry law". As a result, the former Beryozka checkout stores switched to a much less convenient system of trading "by bank transfer", but these changes did not affect the Beryozka currency stores in any way, when payment for the goods ordered in the store had to be made directly in bank by non-cash transfer of the cost of goods from a personal account to a store account (that is, the system of “special departments” that was in effect until 1964 was actually revived).

In the spring of 1991, the "market rate" of the ruble was introduced in the USSR and at the same time the regime of circulation of cash currency was softened (although the effect of Article 88 was not formally canceled), the first official currency exchange offices appeared, and in 1993 the checking accounts of foreign workers in Vnesheconombank were converted into SLE.

Polish bon

CMEA countries

Similar checks existed in all CMEA countries, for example, bonds in Czechoslovakia and Poland, checks in the GDR, etc.

Links

- Stages of a long journey: from fartsovka to checks of Vneshtorgbank of the USSR

| Ruble | |

|---|---|

| Denominations | 2 3 5 7.5 20 40 50 200 250 2500 10,000 15,000 25,000 50,000 100,000 500,000 1,000 000 5,000,000 |

| In circulation | Abkhazia Belarus Transnistria Russia South Ossetia |

| Out of circulation | Latvia Tajikistan |

| Historical currencies of Russia | Banknote ruble Silver ruble Gold ruble Sovznak Chervonets Soviet ruble Pavlovsky ruble Russian ruble |

| Rubles 1917-1924 | Armenian ruble · Azerbaijani ruble · Georgian ruble · Transcaucasian ruble Bukhara ruble Don ruble Kerenki Kuban ruble Odessa ruble · Ruble of the Northwestern Army · Ruble Armed Forces South of Russia · Ruble of the Far Eastern Republic · Ruble of the Northern Region · Siberian ruble Sovznak Turkestan ruble · Harbin ruble · Tsaritsyn ruble· Mitavskaya brand |

| coins | Yekaterinburg ruble Sestroretsk ruble Konstantinovsky ruble Wedding ruble Platinum ruble Kopeyka |

| obsolete coins | Semi-half-dollar · Half-dollar · Denga · Semishnik · Altyn · Pyatak · Gryvennik · Five-altyn · Two-hryvnia · Half-fifty · Fifty · Ruble · Chervonets |

| Varieties and surrogates | Efimok · Ugrian gold · Imperial · Semi-imperial · Brut ruble · Libavian ruble · Ost ruble · Foreign currency ruble · Checks of Vneshtorgbank · Transferable ruble · Ural franc · |

Checks of Vneshposyltorg and Vneshtorgbank as a parallel currency of the USSR March 9th, 2017

Hello dear.

More than once or twice, reading books about the later USSR, starting from Konstantinov, and ending with some very low-grade detectives, you (like me) have repeatedly met a certain currency, which the characters themselves called checks, then bonds, then certificates . Especially often there is a mention of these in the story about our citizens working abroad. These bonds were used to pay salaries, they were saved and coveted :-) Even the disease developed for those who were especially suffering - "chasing" was called.

The point of these checks was to essentially keep the currency out of the hands of people who could earn it. A sort of surrogate for dollars, pounds and marks :-) Suppose people worked somewhere in Africa, and they were paid in local money or currency. But they didn’t give it to their hands, but transferred it to accounts in these same checks. Let's say the father of my friend, a military pilot who provided international debt in Mozambique, received 1,400 Vneshposyltorg checks per month to an account (he could withdraw them in the USSR) and 6,000 Mozambican meticais (in Soviet rubles, this is about 200 rubles) to somehow live there.

Vneshposyltorg checks (let's call them VPT) paid salaries to Soviet citizens who worked abroad: teachers, doctors and military advisers, as well as those who worked under contracts with foreign public and private institutions (hospitals, universities, etc.). Sailors and ordinary employees of embassies sometimes received checks from Vneshtorgbank (VTB). VTB checks were much, much less common.

Booms first appeared in 1965 and it was possible to distinguish 3 of their types. With a blue stripe, with a yellow stripe and without stripes. The former were issued to citizens of the USSR working in the CMEA countries, the latter in the states of both the third world and developed capitalist countries. The difference between them was well known. With blue checks, the crediting ratio to the account was 1:1, and with yellow and stripless checks - 4.6:1. That is, it was more profitable to work and receive money somewhere in Eritrea than in Czechoslovakia. And it caused a lot of problems and discontent.

This led to the fact that in 1974 it was decided to introduce checks of a single sample. And this immediately calmed the passions.

The question arises why and where these checks were needed. How could they be spent? And this is an interesting question. The fact is that a chain of special trading networks was created throughout the Union, where these checks could be spent. In the RSFSR, such stores were called "Birch", in the Ukrainian SSR - "Kashtan", in the Latvian SSR - "Dzintars", and in the Azerbaijan SSR - "Chinar". In addition, there were Torgmortrans shops, some of the special Voentorgs, and the Slybka firm. With some restrictions, through these organizations it was possible to receive so many “nishtyaks” on checks and live quite tolerably. Well, for example, excerpts from the price list of one of the Beryozka stores

Well, of course, it was possible to take scarce goods - from washing machines to cars, and make great money on it.

Such an interesting thing as checks was of particular interest on the black market. And it’s not just that, in the same criminal code of the RSFSR, the sale and purchase of foreign currency was equated to the purchase and sale of certificates (checks) of the VPT, cut-off checks of the “D” and “A” series (Article 88 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR). These were serious crimes and were punishable by long prison terms. But that didn't stop people. The system collapsed only in the early 90s.

What did these checks look like, you ask? Well...it was interesting that even the pennies were in paper form. I have one in my small collection. And they looked like this:

Here is such an interesting form of parallel currency :-)

Have a nice time of the day.